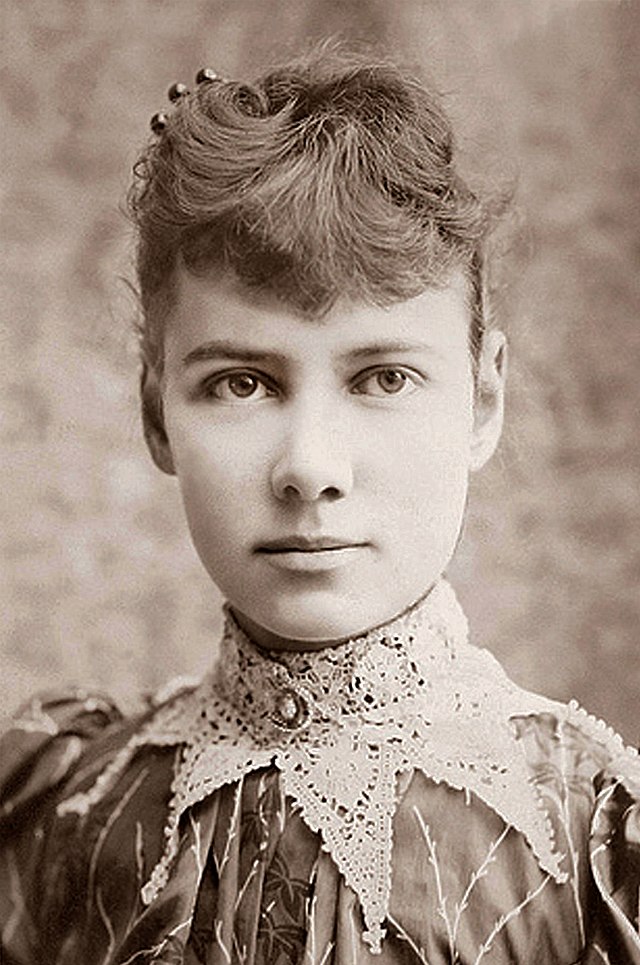

Nellie Bly

A progressive journalist, known for going undercover in various disguises to investigate different institutions in the U.S. Inspired by Jules Verne’s popular 1873 novel, Around the World in Eighty Days, Bly embarked on a solo journey around the world, sponsored by the New York World. Her trip generated much publicity, and she completed it in 72 days. She published her writings about her journey in Around the World in Seventy-Two Days.

Themes

Bly’s narrative is one that challenges conceptions of gender and reflects a growing American feminist ideology of the Progressive Era. She values women’s autonomy and self-reliance, and she uses her journey to prove her independence. However, her view of feminism is very white and Eurocentric; she shows a lack of regard and respect for other cultures and exoticizes the women she encounters abroad.

- “‘It is impossible for you to do it,’ was the terrible verdict. ‘In the first place you are a woman and would need a protector, and even if it were possible for you to travel alone you would need to carry so much baggage that it would detain you in making rapid changes. Besides you speak nothing but English, so there is no use talking about it; no one but a man can do this.’ ‘Very well,’ I said angrily, ‘Start the man, and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him’” (Chapter I).

- “I got everything in at last except the extra dress. Then the question resolved itself into this: I must either add a parcel to my baggage or go around the world in and with one dress. I always hated parcels so I sacrificed the dress, but I brought out a last summer’s silk bodice and after considerable squeezing managed to crush it into the hand-bag” (Chapter I).

- “Then too, did the English railway carriage make me understand why English girls need chaperones. It would make any American woman shudder with all her boasted self-reliance, to think of sending her daughter alone on a trip, even of a few hours’ duration, where there was every possibility that during those hours she would be locked in a compartment with a stranger” (Chapter III).

- “Small wonder the American girl is fearless. She has not been used to so called private compartments in English railway carriages, but to large crowds, and every individual that helps to swell that crowd is to her a protector. When mothers teach their daughters that there is safety in numbers, and that numbers are the body-guard that shield all woman-kind, then chaperones will be a thing of the past, and women will be nobler and better” (Chapter III).

“You may save a young widower before you return,” M. Verne said with a smile.

I smiled with a superior knowledge, as women, fancy free, always will at such insinuations (Chapter IV).

- “Most of the women, whose acquaintance I formed, were very desirous of knowing all about American women, and frequently expressed their admiration for the free American woman, many going so far as to envy me, while admiring my unfettered happiness” (Chapter VI).

- “While standing looking after a train of camels that had just come in loaded with firewood I saw some Egyptian women. They were small in stature and shapelessly clad in black. Over their faces, beginning just below the eyes, they wore black veils that fell almost to their knees. As if fearing that the veil alone would not destroy all semblance of features they wear a thing that spans the face between the hair and the veil down the line of their noses. In some cases this appears to be of gold, and in others it is composed of some black material. One Egyptian woman carried a little naked baby with her. She held it on her hips, its little black legs clinging to her waist much after the fashion of a boy climbing a pole” (Chapter VII).

“To me the sight of these perfect, bronze-like women, with a graceful drapery of thin silk wound about the waist, falling to the knees, and a corner taken up the back and brought across the bust, was most bewitching. On their bare, perfectly modeled arms were heavy bracelets, around the wrist and muscle, most times joined by chains. Bracelets were also worn about the ankles, and their fingers and toes were laden with rings. Sometimes large rings were suspended from the nose, and the ears were almost always outlined with hoop rings, that reached from the inmost edge of the lobe to the top of the ear joining the head. So closely were these rings placed that, at a distance, the ear had the appearance of being rimmed in gold. A more pleasing style of nose ornament was a large gold ornament set in the nostril and fastened there as screw rings fasten in the ear. Still, if that nose ornamentation was more pleasing than the other, the ear adornment that accompanied it was disgusting. The lobe of the ear was split from the ear, and pulled down to such length that it usually rested on the shoulder. The enormous loop of flesh was partially filled with large gold knobs.” (Bly, Ch. VIII).

- “‘Well, you are a lazy girl! You’ll miss your bath and breakfast if you don’t get up the instant,’ was my third greeting. My surprise at the familiarity of the remark got the better of my sleepiness, and I thought. ‘Well, by all that is wonderful, where am I? Am I in school again that a woman dare assume such a tone to me?’ I kept my thoughts to myself, and said stiffly: ‘I generally get up when I feel so inclined.’” (Chapter VI).

“The temple was closed but some priests rushed forth to warn us not step on the sacred old dirty stone-passage leading to it with our shoes on. Its filth would have made it sacred to me with my shoes off! My comrades were told that removing their shoes would give them admission but I should be denied that privilege because I was a woman.

‘Why?’ I demanded, curious to know why my sex in heathen lands should exclude me from a temple, as in America it confines me to the side entrances of hotels and other strange and incommodious things.

‘No, Señora, no mudder,’ the priest said with a positive shake of the head.

‘I’m not a mother!’ I cried so indignantly that my companions burst into laughter, which I joined after a while, but my denials had no effect on the priest. He would not allow me to enter” (Bly, Ch. X).

“On a cold day one would imagine the Japanese were a nation of armless people. They fold their arms up in their long, loose sleeves. A Japanese woman’s sleeves are to her what a boy’s pockets are to him. Her cards, money, combs, hair pins, ornaments and rice paper are carried in her sleeves. Her rice paper is her handkerchief, and she notes with horror and disgust that after using we return our handkerchiefs to our pockets. I think the Japanese women carry everything in their sleeves, even their hearts. Not that they are fickle–none are more true, more devoted, more loyal, more constant, than Japanese women–but they are so guileless and artless that almost any one, if opportunity offers, can pick at their trusting hearts” (Chapter XV).

- “Of course I wanted to go, but I thought lazily that if some of these good people who spend so much time in trying to invent flying machines would only devote a little of the same energy towards promoting a system by which boats and trains would always make their start at noon or afterwards, they would be of greater assistance to suffering humanity” (Chapter II).

- “The weather was very bad, and the sea was rough, but I enjoyed it. My sea-sickness had disappeared, but I had a morbid, haunting idea, that although it was gone, it would come again, still I managed to make myself comfortable” (Chapter II).

- “My escort after giving some order to the porter went out to see about my ticket, so I took a survey of an English railway compartment. The little square in which I sat looked like a hotel omnibus and was about as comfortable. The two red leather seats in it run across the car, one backing the engine, the other backing the rear of the train. There was a door on either side and one could hardly have told that there was a dingy lamp there to cast a light on the scene had not the odor from it been so loud” (Chapter III).

- “There has been so much written and told about the English Channel, that one is inclined to think of it as a stream of horrors. It is also affirmed that even hardy sailors bring up the past when crossing over it, so I naturally felt that my time would come” (Chapter III).

- “But talk about privacy! If it is privacy the English desire so much, they should adopt our American trains, for there is no privacy like that to be found in a large car filled with strangers. Everybody has, and keeps his own place. There is no sitting for hours, as is often the case in English trains, face to face and knees to knees with a stranger, offensive or otherwise, as he may chance to be” (Chapter III).

“The next morning I got up earlier than usual so anxious was I to see the famous Suez Canal. Rushing up on deck, I saw we were passing through what looked like an enormous ditch, enclosed on either side with high sand banks. We seemed to be hardly moving, which made us feel the heat very intensely. They tell me, that according to law, a ship must not travel through the canal at a speed exceeding five knots an hour, because a rapid passage of the ship would make a strong current that would wash in the sand banks. One gentleman, who had traveled all his life, helped us to pass some of the tedious, stifling hours in the canal by telling us the history of it.

It was begun in 1859 and took ten years to build. The work is estimated to have cost nearly £18,250,000, although the poor blacks that were employed to do the labor commanded the lowest possible wages. It is claimed that the lives of 100,000 laborers were sacrificed in the building of this canal, which is only 100 English miles, 88 geographical miles, 5 in length” (Chapter VII).

- “Instead of being the predicted failure, the Oceanic proved a great success. She became the greyhound of the Atlantic, afterwards being transferred to the Pacific in 1875. She is the favorite ship of the O. and O. line, making her voyages with speed and regularity. She retains a look of positive newness and seems to grow younger with years. In November, 1889, she made the fastest trip on record between Yokohama and San Francisco. No expense is spared to make this ship comfortable for the passengers. The catering would be hard to excel by even a first-class hotel. Passengers are accorded every liberty, and the officers do their utmost to make their guests feel at home, so that in the Orient the Oceanic is the favorite ship, and people wait for months so as to travel on her” (Chapter XIV).

Industrialization shaped print and media culture, increasing the rate of production and range of distribution. According to Benedict Anderson, print culture is vital to nation-building, which is predicated on the formation of an imagined community among the people in the nation. He cites newspapers, and especially the ritual of reading one each day, as a tool for creating this imagined community. Bly participated in this form of nation-building through her journalism, which communicated ideas about countries abroad to audiences in the U.S.

- “What gave me the idea? It is sometimes difficult to tell exactly what gives birth to an idea. Ideas are the chief stock in trade of newspaper writers and generally they are the scarcest stock in market, but they do come occasionally[…]This idea came to me one Sunday. I had spent a greater part of the day and half the night vainly trying to fasten on some idea for a newspaper article. It was my custom to think up ideas on Sunday and lay them before my editor for his approval or disapproval on Monday. But ideas did not come that day and three o’clock in the morning found me weary and with an aching head tossing about in my bed. At last tired and provoked at my slowness in finding a subject, something for the week’s work, I thought fretfully: ‘I wish I was at the other end of the earth!’ ‘And why not?’ the thought came: ‘I need a vacation; why not take a trip around the world?’” (Chapter I).

- “I think it is only natural for travelers to take an innocent pleasure in studying the peculiarities of their fellow companions. We were not out many days until everybody that was able to be about had added a little to their knowledge of those that were not. I will not say that the knowledge acquired in that way is of any benefit, nor would I try to say that those passengers who mingled together did not find one another as interesting and as fit subjects for comment. Nevertheless it was harmless and it afforded us some amusement” (Chapter II).

Bly’s trip generated much publicity, and a board game was even created based on her journey. Another newspaper sent out a rival, Elizabeth Bisland, to beat her time. The race was well known by American audiences at home, and people made bets about who they thought would win. The entertainment was akin to what a reality show might be like today!

- “‘Yes,’ he continued briskly; ‘Did you not know? The day you left New York another woman stated out to beat your time, and she’s going to do it. She left here three days ago. You probably met somewhere near the Straits of Malacca. She says she has authority to pay any amount to get ships to leave in advance of their time. Her editor offered one or two thousand dollars to the O. and O. if they would have the Oceanic leave San Francisco two days ahead of time. They would not do it, but they did do their best to get her here in time to catch the English mail for Ceylon. If they had not arrived long before they were due, she would have missed that boat, and so have been delayed ten days. But she caught the boat and left three days ago, and you will be delayed here five days.’” (Chapter XII).

“I promised my editor that I would go around the world in seventy-five days, and if I accomplish that I shall be satisfied,” I stiffly explained. “I am not racing with anyone. I would not race. If someone else wants to do the trip in less time, that is their concern. If they take it upon themselves to race against me, it is their lookout that they succeed. I am not racing. I promised to do the trip in seventy-five days, and I will do it; although had I been permitted to make the trip when I first proposed it over a year ago, I should then have done it in sixty days.” (Chapter XII).

Bly participates in a stereotypical way of viewing the East known as Orientalism, which according to Stuart Hall and Edward Said, forges a European (or Western in which the U.S. is included) and non-European binary. According to Said, “far from simply reflecting what the countries of the Near East were actually like, Orientalism was the discourse by which European culture was able to manage – and even produce – the Orient politically, sociologically, militarily, ideologically, scientifically, and imaginatively” (Hall 259). This could look like exoticizing, eroticizing, and fetishizing the places and people in this area of the world. Bly continues to do so throughout her narrative, and the following quotes reflect this gaze.

- “Hardly had the anchor dropped than the ship was surrounded with a fleet of small boats, steered by half-clad Arabs, fighting, grabbing, pulling, yelling in their mad haste to be first. I never in my life saw such an exhibition of hungry greed for the few pence they expected to earn by taking the passengers ashore. Some boatmen actually pulled others out of their boats into the water in their frantic endeavors to steal each other’s places. When the ladder was lowered, numbers of them caught it and clung to it as if it meant life or death to them, and here they clung until the captain was compelled to order some sailors to beat the Arabs off, which they did with long poles, before the passengers dared venture forth. This dreadful exhibition made me feel that probably there was some justification in arming one’s self with a club” (Chapter VII).

- “While standing looking after a train of camels that had just come in loaded with firewood I saw some Egyptian women. They were small in stature and shapelessly clad in black. Over their faces, beginning just below the eyes, they wore black veils that fell almost to their knees. As if fearing that the veil alone would not destroy all semblance of features they wear a thing that spans the face between the hair and the veil down the line of their noses. In some cases this appears to be of gold, and in others it is composed of some black material. One Egyptian woman carried a little naked baby with her. She held it on her hips, its little black legs clinging to her waist much after the fashion of a boy climbing a pole” (Chapter VII).

- “The man in charge of the boat that carried us to land was a small black fellow with the thinnest legs I ever saw. Somehow they reminded me of smoked herrings, they were so black, flat and dried looking. He was very gay notwithstanding his lack of weight. Around his neck and over his bare breast were twined strings of beads, black and gold and silver. Around his waist was a highly colored sash, and on his arms and ankles were heavy bracelets, while his fingers and toes seemed to be trying to outdo one another in the way of rings. He spoke English quite well, and to my rather impertinent question as to what number constituted his family told me that he had three wives and eleven children, which number, he added piously, by the grace of the power of his faith, he hoped to increase” (Chapter VIII).

- “To me the sight of these perfect, bronze-like women, with a graceful drapery of thin silk wound about the waist, falling to the knees, and a corner taken up the back and brought across the bust, was most bewitching. On their bare, perfectly modeled arms were heavy bracelets, around the wrist and muscle, most times joined by chains. Bracelets were also worn about the ankles, and their fingers and toes were laden with rings. Sometimes large rings were suspended from the nose, and the ears were almost always outlined with hoop rings, that reached from the inmost edge of the lobe to the top of the ear joining the head. So closely were these rings placed that, at a distance, the ear had the appearance of being rimmed in gold. A more pleasing style of nose ornament was a large gold ornament set in the nostril and fastened there as screw rings fasten in the ear. Still, if that nose ornamentation was more pleasing than the other, the ear adornment that accompanied it was disgusting. The lobe of the ear was split from the ear, and pulled down to such length that it usually rested on the shoulder. The enormous loop of flesh was partially filled with large gold knobs.” (Chapter VIII).

- “They [the Sinhalese waiters] managed to speak English very well and understood everything that was said to them. They are not unpleasing people, being small of stature and fine of feature, some of them having very attractive, clean-cut faces, light bronze in color. They wore white linen apron-like skirts and white jackets” (Chapter IX).

- “There are no sidewalks in Singapore, and blue and white in the painting of the houses largely predominate over other colors. Families seem to occupy the second story, the lower being generally devoted to business purposes. Through latticed windows we got occasional glimpses of peeping Chinese women in gay gowns, Chinese babies bundled in shapeless, wadded garments, while down below through widely opened fronts we could see people pursuing their trades. Barbering is the principal trade. A chair, a comb, a basin and a knife are all the tools a man needs to open shop, and he finds as many patrons if he sets up shop in the open street as he would under shelter. Sitting doubled over, Chinamen have their heads shaven back almost to the crown, when a spot about the size of a tiny saucer is left to bear the crop of hair which forms the pig-tail. When braided and finished with a silk tassel the Chinaman’s hair is “done” for the next fortnight” (Chapter X).

- “The town seemed in a state of untidiness, the road was dirty, the mobs of natives we met were filthy, the houses were dirty, the numberless boats lying along the wharf, which invariably were crowded with dirty people, were dirty, our carriers were dirty fellows, their untidy pig-tails twisted around their half-shaven heads. They trotted steadily ahead, snorting at the crowds of natives we met to clear the way. A series of snorts or grunts would cause a scattering of natives more frightened than a tie-walker would be at the tooting of an engine’s whistle” (Chapter XII).

- “Ah Cum is more comely in features than most Mongolians, his nose being more shapely and his eyes less slit-like than those of most of his race. He had on his feet beaded black shoes with white soles. His navy-blue trousers, or tights, more properly speaking, were tied around the ankle and fitted very tight over most of the leg. Over this he wore a blue, stiffly starched shirt-shaped garment, which reached his heels, while over this he wore a short padded and quilted silk jacket, somewhat similar to a smoking jacket. His long, coal-black queue, finished with a tassel of black silk, touched his heels, and on the spot where the queue began rested a round black turban” (Chapter XIII).

- “I was warned not to be surprised if the Chinamen should stone me while I was in Canton. I was told that Chinese women usually spat in the faces of female tourists when the opportunity offered. However, I had no trouble. The Chinese are not pleasant appearing people; they usually look as if life had given them nothing but trouble; but as we were carried along the men in the stores would rush out to look at me. They did not take any interest in the men with me, but gazed at me as if I was something new. They showed no sign of animosity, but the few women I met looked as curiously at me, and less kindly” (Chapter XIII).

- “After seeing Hong Kong with its wharfs crowded with dirty boats manned by still dirtier people, and its streets packed with a filthy crowd, Yokohama has a cleaned-up Sunday appearance. Travelers are taken from the ships, which anchor some distance out in the bay, to the land in small steam launches. The first-class hotels in the different ports have their individual launches, but like American hotel omnibuses, while being run by the hotel to assist in procuring patrons, the traveler pays for them just the same. An import as well as an export duty is charged in Japan, but we passed the custom inspectors unmolested. I found the Japanese jinricksha men a gratifying improvement upon those I seen from Ceylon to China. They presented no sight of filthy rags, nor naked bodies, nor smell of grease. Clad in neat navy-blue garments, their little pudgy legs encased in unwrinkled tights, the upper half of their bodies in short jackets with wide flowing sleeves; their clean, good-natured faces, peeping from beneath comical mushroom-shaped hats; their blue-black, wiry locks cropped just above the nape of the neck, they offered a striking contrast to the jinricksha men of other countries. Their crests were embroidered upon the back and sleeves of their top garment as are the crests of every man, woman and child in Japan.” (Chapter XV).

- “I always have an inclination to laugh when I look at the Japanese men in their native dress. Their legs are small and their trousers are skin tight. The upper garment, with its great wide sleeves, is as loose as the lower is tight. When they finish their “get up” by placing their dish-pan shaped hat upon their heads, the wonder grows how such small legs can carry it all! Stick two straws in one end of a potato, a mushroom in the other, set it up on the straws and you have a Japanese in outline. Talk about French heels! The Japanese sandal is a small board elevated on two pieces of thin wood fully five inches in height. They make the people look exactly as if they were on stilts. These queer shoes are fastened to the foot by a single strap running between toes number one and two, the wearer when walking necessarily maintaining a sliding instead of an up and down movement, in order to keep the shoe on” (Chapter XV).

- “The Japanese are the direct opposite to the Chinese. The Japanese are the cleanliest people on earth, the Chinese are the filthiest; the Japanese are always happy and cheerful, the Chinese are always grumpy and morose; the Japanese are the most graceful of people, the Chinese the most awkward; the Japanese have few vices, the Chinese have all the vices in the world; in short, the Japanese are the most delightful of people, the Chinese the most disagreeable” (Chapter XV).

- “The prettiest sight in Japan, I think, is the native streets in the afternoons. Men, women and children turn out to play shuttle-cock and fly kites. Can you imagine what an enchanting sight it is to see pretty women with cherry lips, black bright eyes, ornamented, glistening hair, exquisitely graceful gowns, tidy white-stockinged feet thrust into wooden sandals, dimpled cheeks, dimpled arms, dimpled baby hands, lovely, innocent, artless, happy, playing shuttlecock in the streets of Yokohama?” (Chapter XV)

“‘Very well,’ I said angrily, ‘Start the man, and I'll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him’” (Chapter I).

Image: William Merritt Chase, A Friendly Call, 1895, from Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art

Places Visited

London

Out of all the places Bly traveled, she compares London most to America. She writes of its railroad system, architecture, and history with a sense of respect. London even makes her reflect on the “dreadful” streets of New York in comparison; although, she remains partial to New York. Her descriptions of London, compared to other places farther East in her journey, reflect a Eurocentric supremacy and gaze that she carries with her throughout the trip.

- “How are these streets compared with those of New York?” was the first question that broke the silence after our leaving the station. “They are not bad,” I said with a patronizing air, thinking shamefacedly of the dreadful streets of New York, although determined to hear no word against them. Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament were pointed out to me, and the Thames, across which we drove. I felt that I was taking what might be called a bird’s-eye view of London” (Chapter III).

- “‘How are these streets compared with those of New York?’ was the first question that broke the silence after our leaving the station. ‘They are not bad,’ I said with a patronizing air, thinking shamefacedly of the dreadful streets of New York, although determined to hear no word against them. Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament were pointed out to me, and the Thames, across which we drove. I felt that I was taking what might be called a bird’s-eye view of London” (Chapter III).

After leaving London, Bly crosses the English Channel to Boulogne, France. Soon after she arrives, she boards a train to Amiens to meet Jules Verne

Boulogne

- “I was in France now, and I began to wonder now what would have been my fate if I had been alone as I had expected. I knew my companion spoke French, the language that all the people about us were speaking, so I felt perfectly easy on that score as long as he was with me” (Chapter III).

- “We traveled from Boulogne to Amiens in a compartment with an English couple and a Frenchman. There was one foot-warmer and the day was cold. We all tried to put our feet on the one foot-warmer and the result was embarrassing. The Frenchman sat facing me and as I was conscious of having tramped on someone’s toes, and as he looked at me angrily all the time above the edge of his newspaper, I had a guilty feeling of knowing whose toes had been tramped on” (Chapter III).

Amiens

- “It was early evening. As we drove through the streets of Amiens I got a flying glimpse of bright shops, a pretty park, and numerous nurse maids pushing baby carriages about” (Chapter IV).

- “I leaned over the desk and looked out of the little latticed window which he had thrown open. I could see through the dusk the spire of a cathedral in the distance, while stretching down beneath me was a park, beyond which I saw the entrance to a railway tunnel that goes under M. Verne’s house, and through which many Americans travel every year, on their way to Paris” (Chapter IV)

Brindisi

Like other places in Europe, Bly held a certain respect for Italy. She was excited to see Italy because of what she heard about its beauty.

- “All day I traveled through Italy–sunny Italy, along the Adriatic Sea. The fog still hung in a heavy cloud over the earth, and only once did I get a glimpse of the land I had heard so much about. It was evening, just at the hour of sunset, when we stopped at some station. I went out on the platform, and the fog seemed to lift for an instant, and I saw on one side a beautiful beach and a smooth bay dotted with boats bearing oddly-shaped and brightly-colored sails, which somehow looked to me like mammoth butterflies, dipping, dipping about in search of honey. Most of the sails were red, and as the sun kissed them with renewed warmth, just before leaving us in darkness, the sails looked as if they were composed of brilliant fire” (Chapter V).

Bly participates in a stereotypical way of viewing the so-called “Near East” known as Orientalism (Hall 259). Orientalism forges a European (or Western in which the U.S. is included) and non-European binary. According to Edward Said, “far from simply reflecting what the countries of the Near East were actually like, Orientalism was the discourse by which European culture was able to manage – and even produce – the Orient politically, sociologically, militarily, ideologically, scientifically, and imaginatively” (Hall 259). This could look like exoticizing, eroticizing, and fetishizing the places and people in this area of the world. She continues to do so throughout her narrative. The following places contain quotes that reflect this kind of gaze.

Port Said

-

“Hardly had the anchor dropped than the ship was surrounded with a fleet of small boats, steered by half-clad Arabs, fighting, grabbing, pulling, yelling in their mad haste to be first. I never in my life saw such an exhibition of hungry greed for the few pence they expected to earn by taking the passengers ashore. Some boatmen actually pulled others out of their boats into the water in their frantic endeavors to steal each other’s places. When the ladder was lowered, numbers of them caught it and clung to it as if it meant life or death to them, and here they clung until the captain was compelled to order some sailors to beat the Arabs off, which they did with long poles, before the passengers dared venture forth. This dreadful exhibition made me feel that probably there was some justification in arming one’s self with a club” (Chapter VII).

- “The next morning I got up earlier than usual so anxious was I to see the famous Suez Canal. Rushing up on deck, I saw we were passing through what looked like an enormous ditch, enclosed on either side with high sand banks. We seemed to be hardly moving, which made us feel the heat very intensely. They tell me, that according to law, a ship must not travel through the canal at a speed exceeding five knots an hour, because a rapid passage of the ship would make a strong current that would wash in the sand banks. One gentleman, who had traveled all his life, helped us to pass some of the tedious, stifling hours in the canal by telling us the history of it” (Chapter VII).

-

“The next morning I got up earlier than usual so anxious was I to see the famous Suez Canal. Rushing up on deck, I saw we were passing through what looked like an enormous ditch, enclosed on either side with high sand banks. We seemed to be hardly moving, which made us feel the heat very intensely. They tell me, that according to law, a ship must not travel through the canal at a speed exceeding five knots an hour, because a rapid passage of the ship would make a strong current that would wash in the sand banks. One gentleman, who had traveled all his life, helped us to pass some of the tedious, stifling hours in the canal by telling us the history of it.

It was begun in 1859 and took ten years to build. The work is estimated to have cost nearly £18,250,000, although the poor blacks that were employed to do the labor commanded the lowest possible wages. It is claimed that the lives of 100,000 laborers were sacrificed in the building of this canal, which is only 100 English miles, 88 geographical miles, 5 in length” (Chapter VII).

(In modern day Yemen)

Right as Bly arrives in Aden, she begins commenting on the bodies of the people she sees around her, an example of Orientalism and “Othering” in this location.

- “To me the sight of these perfect, bronze-like women, with a graceful drapery of thin silk wound about the waist, falling to the knees, and a corner taken up the back and brought across the bust, was most bewitching. On their bare, perfectly modeled arms were heavy bracelets, around the wrist and muscle, most times joined by chains. Bracelets were also worn about the ankles, and their fingers and toes were laden with rings. Sometimes large rings were suspended from the nose, and the ears were almost always outlined with hoop rings, that reached from the inmost edge of the lobe to the top of the ear joining the head. So closely were these rings placed that, at a distance, the ear had the appearance of being rimmed in gold. A more pleasing style of nose ornament was a large gold ornament set in the nostril and fastened there as screw rings fasten in the ear. Still, if that nose ornamentation was more pleasing than the other, the ear adornment that accompanied it was disgusting. The lobe of the ear was split from the ear, and pulled down to such length that it usually rested on the shoulder. The enormous loop of flesh was partially filled with large gold knobs.” (Chapter VIII).

- “Near the pier were shops run by Parsees. A hotel, post-office and telegraph office are located in the same place. The town of Aden is five miles distant. We hired a carriage and started at a good pace, on a wide, smooth road that took us along the beach for a way, passing low rows of houses, where we saw many miserable, dirty-looking natives; passed a large graveyard, liberally filled, which looked like the rest of that stony point, bleak, black and bare, the graves often being shaped by cobblestones.The roads at Aden are a marvel of beauty. They are wide and as smooth as hardwood, and as they twist and wind in pleasing curves up the mountain, they are made secure by a high, smooth wall against mishap. Otherwise their steepness might result in giving tourists a serious roll down a rough mountain-side” (Chapter VIII).

(Modern day Sri Lanka)

Colombo

Nellie Bly again describes the people around her, with a focus on appearance. It does not seem like a coincidence that her praise of these people coincides with the fact that they speak English, as well as the fact that they are serving her.

- “They [the Sinhalese waiters] managed to speak English very well and understood everything that was said to them. They are not unpleasing people, being small of stature and fine of feature, some of them having very attractive, clean-cut faces, light bronze in color. They wore white linen apron-like skirts and white jackets” (Chapter IX)

- “With all our impatience we could not fail to be impressed with the beauties of Colombo and the view from the deck of our incoming steamer. As we moved in among the beautiful ships laying at anchor, we could see the green island dotted with low arcaded buildings which looked, in the glare of the sun, like marble palaces. In the rear of us was the blue, blue sea, jumping up into little hills that formed into snow drifts which softly sank into the blue again. Forming the background to the town was a high mountain, which they told us was known as Adam’s Peak. The beach, with a forest of tropical trees, looked as if it started in a point away out in the sea, curving around until near the harbor it formed into a blunt point, the line of which was carried out to sea by a magnificent breakwater surmounted by a light-house. Then the land curved back again to a point where stood a signal station, and on beyond a wide road ran along the water’s edge until it was lost at the base of a high green eminence that stood well out over the sea, crowned with a castle-like building glistening in the sunlight” (Chapter IX).

- “I visited at the temples in Colombo, finding little of interest, and always having to pay liberally for the privilege of looking about. One day I went to the Buddhist college, and while there I met the famous high priest of Ceylon. He was sitting on a verandah, that surrounded his low bungalow, writing on a table placed before him. His gown consisted of a straight piece of old gold silk wrapped deftly around the body and over the waist. The silk had fallen to his waist, but after he greeted us he pulled it up around his shoulders. He was a copper-colored old fellow, with gray hair that was shaved very close to the head” (Chapter IX).

- “Colombo reminded me of Newport, R. I. Possibly–in my eyes, at least–Colombo is more beautiful. The homes may not be as expensive, but they are more artistic and picturesque. The roads are wide and perfect; the view of the sea is grand, and while unlike in its tropical aspect, still there is something about Colombo that recalls Newport” (Chapter IX)

(In modern day Malaysia)

Departing from Colombo, Bly traveled across the Bay of Bengal to Penang, which is in modern-day Malaysia. At the time, Penang was part of the Straits Settlements, a group of British territories in what we now think of as Southeast Asia. It was also referred to as Prince of Wales Island at the time.

- “The next day we anchored at Penang, or Prince of Wales Island, one of the Straits Settlements. As the ship had such a long delay at Colombo, it was said that we would have but six hours to spend on shore. With an acquaintance as escort, I made my preparations and was ready to go to land the moment we anchored. We went ashore in a Sampan, an oddly shaped flat boat with the oars, or rather paddles, fastened near the stern. The Malay oarsman rowed hand over hand, standing upright in the stern, his back turned towards us as well as the way we were going. Frequently he turned his head to see if the way was clear, plying his oars industriously all the while. Once landed he chased us to the end of the pier demanding more money, although we had paid him thirty cents, just twenty cents over and above the legal fare” (Chapter X).

-

“English is spoken less in Penang than in any port I visited. A native photographer, when I questioned him about it, said:

‘The Malays are proud, Miss. They have a language of their own and they are too proud to speak any other.’

That photographer knew how to use his English to advantage. He showed me cabinet-sized proofs for which he asked one dollar each.

‘One dollar!’ I exclaimed in astonishment, ‘That is very high for a proof.’

‘If Miss thinks it is too much she does not need to buy. She is the best judge of how much she can afford to spend,’ he replied with cool impudence.

‘Why are they so expensive?’ I asked, nothing daunted by his impertinence.

‘I presume because Penang is so far from England,’ he rejoined, carelessly” (Chapter X).

- “There are no sidewalks in Singapore, and blue and white in the painting of the houses largely predominate over other colors. Families seem to occupy the second story, the lower being generally devoted to business purposes. Through latticed windows we got occasional glimpses of peeping Chinese women in gay gowns, Chinese babies bundled in shapeless, wadded garments, while down below through widely opened fronts we could see people pursuing their trades. Barbering is the principal trade. A chair, a comb, a basin and a knife are all the tools a man needs to open shop, and he finds as many patrons if he sets up shop in the open street as he would under shelter. Sitting doubled over, Chinamen have their heads shaven back almost to the crown, when a spot about the size of a tiny saucer is left to bear the crop of hair which forms the pig-tail. When braided and finished with a silk tassel the Chinaman’s hair is ‘done’ for the next fortnight” (Chapter X).

-

“The temple was closed but some priests rushed forth to warn us not step on the sacred old dirty stone-passage leading to it with our shoes on. Its filth would have made it sacred to me with my shoes off! My comrades were told that removing their shoes would give them admission but I should be denied that privilege because I was a woman.

‘Why?’ I demanded, curious to know why my sex in heathen lands should exclude me from a temple, as in America it confines me to the side entrances of hotels and other strange and incommodious things.

‘No, Señora, no mudder,’ the priest said with a positive shake of the head.

‘I’m not a mother!’ I cried so indignantly that my companions burst into laughter, which I joined after a while, but my denials had no effect on the priest. He would not allow me to enter” (Chapter X).

-

“The town seemed in a state of untidiness, the road was dirty, the mobs of natives we met were filthy, the houses were dirty, the numberless boats lying along the wharf, which invariably were crowded with dirty people, were dirty, our carriers were dirty fellows, their untidy pig-tails twisted around their half-shaven heads. They trotted steadily ahead, snorting at the crowds of natives we met to clear the way. A series of snorts or grunts would cause a scattering of natives more frightened than a tie-walker would be at the tooting of an engine’s whistle” (Chapter XII).

- “We first saw the city of Hong Kong in the early morning. Gleaming white were the castle-like homes on the tall mountain side. We fired a cannon as we entered the bay, the captain saying that this was the custom of mail ships. A beautiful bay was this magnificent basin, walled on every side by high mountains” (Chapter XII).

- “Hong Kong is strangely picturesque. It is a terraced city, the terraces being formed by the castle-like, arcaded buildings perched tier after tier up the mountain’s verdant side. The regularity with which the houses are built in rows made me wildly fancy them a gigantic staircase, each stair made in imitation of castles” (Chapter XII).

- “The town seemed in a state of untidiness, the road was dirty, the mobs of natives we met were filthy, the houses were dirty, the numberless boats lying along the wharf, which invariably were crowded with dirty people, were dirty, our carriers were dirty fellows, their untidy pig-tails twisted around their half-shaven heads. They trotted steadily ahead, snorting at the crowds of natives we met to clear the way. A series of snorts or grunts would cause a scattering of natives more frightened than a tie-walker would be at the tooting of an engine’s whistle” (Chapter XII).

- “I promised my editor that I would go around the world in seventy-five days, and if I accomplish that I shall be satisfied,” I stiffly explained. “I am not racing with anyone. I would not race. If someone else wants to do the trip in less time, that is their concern. If they take it upon themselves to race against me, it is their lookout that they succeed. I am not racing. I promised to do the trip in seventy-five days, and I will do it; although had I been permitted to make the trip when I first proposed it over a year ago, I should then have done it in sixty days.” (Chapter XII).

Yokohama

Finally, after delays, Bly arrived in Yokohama, Japan on December 28, traveling by steamship across the East China Sea. The way Bly described Yokohama was different from other places in the East, however, it was still an Orientalist gaze. She again describes the bodies and appearance of the people she encounters, this time referring to their “cleanliness” as a sign of morality.

“I found the Japanese jinricksha men a gratifying improvement upon those I seen from Ceylon to China. They presented no sight of filthy rags, nor naked bodies, nor smell of grease. Clad in neat navy-blue garments, their little pudgy legs encased in unwrinkled tights, the upper half of their bodies in short jackets with wide flowing sleeves; their clean, good-natured faces, peeping from beneath comical mushroom-shaped hats; their blue-black, wiry locks cropped just above the nape of the neck, they offered a striking contrast to the jinricksha men of other countries.” (Chapter XV).

“On a cold day one would imagine the Japanese were a nation of armless people. They fold their arms up in their long, loose sleeves. A Japanese woman’s sleeves are to her what a boy’s pockets are to him. Her cards, money, combs, hair pins, ornaments and rice paper are carried in her sleeves. Her rice paper is her handkerchief, and she notes with horror and disgust that after using we return our handkerchiefs to our pockets. I think the Japanese women carry everything in their sleeves, even their hearts. Not that they are fickle–none are more true, more devoted, more loyal, more constant, than Japanese women–but they are so guileless and artless that almost any one, if opportunity offers, can pick at their trusting hearts” (Chapter XV).

- “They have two very pretty customs in Japan. The one is decorating their houses in honor of the new year, and the other celebrating the blossoming of the cherry trees. Bamboo saplings covered with light airy foliage and pinioned so as to incline towards the middle of the street, where meeting they form an arch, make very effective decorations. Rice trimmings mixed with sea-weed, orange, lobster and ferns are hung over every door to insure a plentiful year, while as sentinels on either side are large tubs, in which are three thick bamboo stalks, with small evergreen trees for background” (Chapter XV).

- “In Yokohama, I went to Hundred Steps, at the top of which lives a Japanese belle, Oyuchisan, who is the theme for artist and poet, and the admiration of tourists. One of the pleasant events of my stay was the luncheon given for me on the Omaha, the American war vessel lying at Yokohama. I took several drives, enjoying the novelty of having a Japanese running by the horses’ heads all the while. I ate rice and eel. I visited the curio shops, one of which is built in imitation of a Japanese house, and was charmed with the exquisite art I saw there; in short, I found nothing but what delighted the finer senses while in Japan” (Chapter XV).

“‘Hurrah for Nellie Bly!’ The crowd clapped hands and cheered, and after making way for me to pass to the dining-room, pressed forward and cheered again, crowding to the windows at last to watch me eat. When I sat down, several dishes were put before me bearing the inscription, ‘Success, Nellie Bly’” (Chapter XVI).

Image: Roberet Frederick Blum, The Ameya, 1892. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Secondary Sources

- Matthew Goodman, Eighty Days

- Daniel T. Rogers, Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age

- Marilyn Lake, Progressive New World: How Settler Colonialism and Transpacific Exchange Shaped American Reform

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities

- Jules Verne, Around the World in Eighty Days

- Stuart Hall, "The Spectacle of the Other"

- Matthew Fry Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917