Annie Smith Peck

Peck, a mountaineer and naturalist, traveled to Peru in 1903 to attempt reaching the summit of the highest peak in the Western hemisphere. She endured many trials and tribulations due to the natural dangers which accompanied her lofty goals, and she contributed to the feminist movements of the 19th century.

Image Gallery

Themes

Peck commented frequently on the churches and religious ceremonies she witnessed during her travels. She seemed fascinated by the differences in the religious culture in Peru and Bolivia compared to America. Although she seldomly discussed her own religious beliefs, she wrote that she ordered a cross to be built to plant on the summit of Mt. Illampu. Even though she did not explicitly mention her own Christianity, she did advocate for the expansion of Christianity in South America. She believed it would be beneficial for social progress.

“It is evident that the civilization and Christianity of these indians does not go very deep. They are little altered from four centuries ago, except probably for the worse, imitating the vices more than the virtues of their conquerors, as happens generally. Education is sadly needed, but with the absence of material development and the small revenue it is hardly surprising that so little has been done in this direction. The old idea of keeping the lower classes in a state of ignorance no doubt formerly prevailed here as in other parts of the world, but the new one is growing that for the full development of a country there must be general education, even of the laborers” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 77).

“The dwellings of the poorer people in the outlying actions, with floors of dirt or brick, are in striking contrast. Such people sleep on the floor and many appear to sit there as well. The proportion of Indians is far less than in La Paz, most of the people having and a mixture of Spanish blood. Among the residents are many families of wealth who travel in Europe, speak several languages, have homes elegantly furnished, and are most agreeable to meet socially (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 87).

“The people are extremely religious, being called, in fact, the most bigoted in Peru if not in all South America. There is no objection to foreigners worshipping privately in their own fashion, but they strongly disapprove of any efforts to proselyte others. The cathedral has a simple, imposing interior, the exterior cannot be so regarded” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 87-8).

“Of frequent occurrence are religious processions, which are conducted with great ceremony. While I was waiting or a steamer, there fell a holy day in honor of the Virgin as patron saint of the army” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 88).

“After a three hours’ ride, mostly through a desert region, we reached a village called Nepeña, where we were compelled to make a not unwelcome pause, in order not to desecrate by passing on horseback a religious procession which was in progress in honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 162).

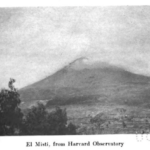

Peck wrote about her passion for nature as her original purpose behind traveling to South America. The way she wrote about the scenery in South America makes her love of nature apparent. She frequently goes into detail about the vegetation or the temperature with such specificity, illuminating her careful observations of her surroundings. Whether she was doing this to prove her validity as a scientist or purely out of passion, she dedicated a significant portion of her time in South America to the physical properties of the landscape. Even more, Peck climbed at a very advanced level, so much of her travel narratives recount the dangers that nature presented to her while climbing.

“No one is acquainted with mountains who sees them only from valleys or from a railway train; the wooded and grassy slopes, the moraines and glacier, the rocks and cliffs, the precipices, the snow fields, the cornice and crevasse, the wide expanse of earth and heaven, the stillness and solitude, the calm and peace, so different from the ever restless sea,—these should attract and will charm every soul with a love of beauty and grandeur; while this most exhilarating form of exercise, bu strengthening the heart and lungs, will renew the youth of everyone who is able to walk, if he go carefully and gradually according to his measure, whether that be 5,000 or 15,000 feet” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. ix).

“The coast presents, for the most part, a study in browns and yellows, diversified by occasional patches of green, varying in size according to that of the stream ad the amount of irrigation in the valley” A Search for the Apex of America, p. 16).

“Most of my previous equipment had been sold in La Paz, so I must procure another. This was hastily accomplished and on Tuesday, June 21, 1904, I sailed again from New York for the ascent of the great Illampu, if less confidently than before with good hope that though alone, I might be able to accomplish more than the year previous. I certainly could not do less. My plans were broader than in 1903. On that journey I had heard of other mountains which some persons thought were more lofty than Sorata; a volcano, Sajama, apparently of great height, near the border of Bolivia and Chile, and Mt. Huascarán in Peru, the latter said to have an altitude of 25,000 feet. If my funds proved sufficient I intended to investigate these mountains also, and I hoped to be able to reach the top of one of them” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 123).

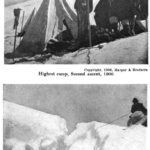

“Now with daily recurring snow storms, it was folly to think of another attempt, so I prepared to return home feeling that, if I had not accomplished all I desired, I had done enough to show that I was not insane in believing that I was personally capable, with proper assistance, of making the ascent of a great mountain. I should bring to the attention of Alpinists a new and accessible territory, worth visiting not merely to make a record, but to behold a glorious collection of mountain peaks, some of which will long defy their would-be conquerors” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 201).

“To me these stately mountains are far more alluring than the treacherous, restless sea. They will not swallow you up, nor crush you with stones or avalanches, if you take them in the right mood and season. They are calm, tranquil, uplifting. If one might sit awhile and gaze!” (299).

“I sat perched half way on the wall, unable to see the men above or those below, and obliged to remain motionless on my icy seat, where a fall backwards would predicate me into a black and profound abyss, and a slip forward to a greater depth down the face of the wall into some immense cavern or Bergschrund at the bottom. So long as I sat still, I was safe, though when at last Lucas came down, I had to crowd myself into the smallest possible space in order to give him room to pass by” (A Search for the Apex of America 352-53).

“The triangulation was not long delayed. Solely in the interest of science, it is said an expedition of three French engineers was sent from Paris to Peru to secure the altitude of this one mountain. Apparently the work was done with an extreme care which presupposes accurate measurement; yet $13,000 seems a large sum to spend for the triangulation of a single mountain which it cost but $3,000 to climb. With $1,000 more for my expedition, I would have been able with an assistant to triangulate the peak myself. With $12,000 additional I could have triangulated and climbed many mountains and accomplished other valuable exploration” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 358).

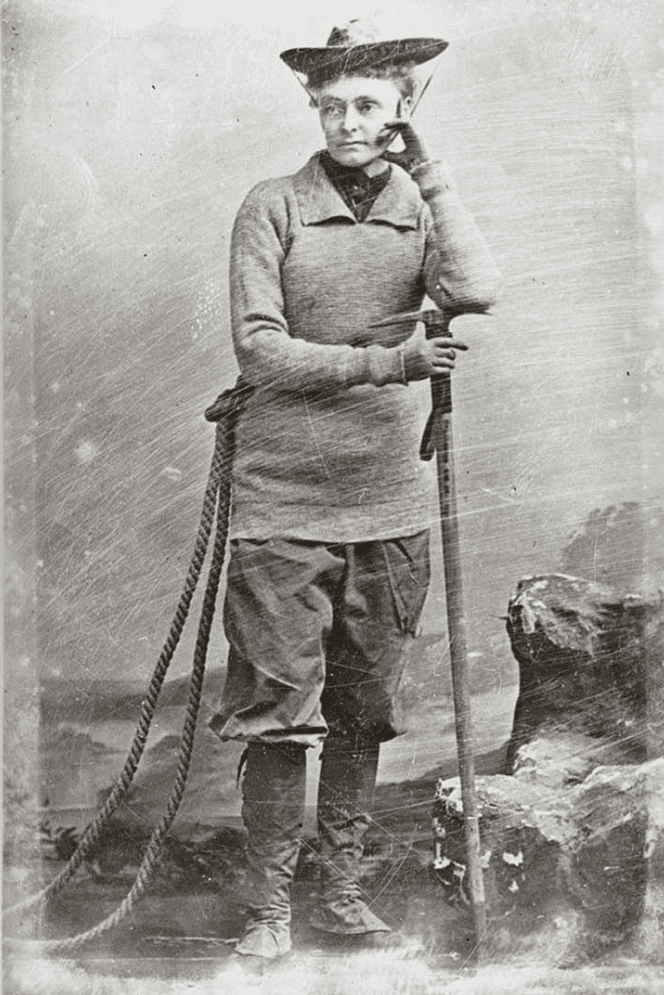

Peck was one of few woman travelers during the 19th century who was mountaineering at such a high level. At the time of her travels, it was quite uncommon for women to travel without the company of a husband. Peck did travel with male, Swiss guides and wrote about feeling the need to prove herself as a woman in the climbing industry. She was a stark advocate for women achieving equal rights to men, and her mere presence in the industry–not to mention her choice to wear pants and carry her own equipment–was provocative.

“To all who had faith in my ability to win ultimate success of who have rejoined in my triumph, I would express the hope that they may be encouraged on future occasions to aid women everywhere in obtaining equal opportunity with men; justice and not favor” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. VII).

“What I had begun merely for my own pleasure I continued with a scientific purpose also, taking with me to the top of Orizaba a mercurial barometer to measure the altitude. The result of my observations as calculated by the United States Weather Bureau, indicates a height of 18,660 feet. My next thought was to do a little genuine exploration, to conquer a virgin peak, to attain some height where no man had previously stood” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. X).

“During breakfast, which was at half past twelve, we had a long conversation in regard to the status of women in our respective countries. An agreeable and cultivated French priest who was present expressed his opinion in opposition to women being allowed so much freedom as in the United States, though he approved of their having broader lives than in Peru” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 163).

“For she was a suffragist, if not a suffragettes (the latter had not been heard of in those days), an ardent believer in the higher education of woman and eager to learn of the greater freedom and other advantages enjoyed by the women of the United States” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 175).

“I said everything to them in Spanish that I knew how; that they were without shame or pity, no men and worse than women; but all in vain” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 253).

Though it would thus appear that Huascarán is not so lofty as I had hoped, my ten long years of effort had culminated in the conquest of a mountain at least 1,500 feet higher than Mt. McKinley, and 2,500 feet higher than any man residing in the United States had climbed. With this I must be content until opportunity is offered to investigate some other possibilities in regard to the Apex of America (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 358).

“A woman who has done good work in the scholastic world doesn’t like to be called a good woman scholar. Call her a good scholar and let it go at that. Tracking the figures given for Mount Huascarán by the triangulation, I have climbed 1,500 feet higher than any man in the United States. Don’t call me a woman mountain climber” (The New York Times, 1911).

Peck’s notes on the local people she interacted with, as well as her opinions on the efficiency of the economy in Peru and Bolivia, reveal how her identity as a wealthy, white, American woman, colored her perspectives abroad. Even though she was a leader in American feminist organizations, she carried racist notions of the societies she interacted with. In many of the places she visited, she recounted her journey with a sense of entitlement, and she perpetuates racist stereotypes of people in South America which portrayed them as lazy and inferior.

“Many natives came on board ship with various articles to sell, parquets, mocking birds, fruits, ancient and modern pottery, and Panama hats; for Panam hats, be it understood, were never made in Panama” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 15).

“The Indian women wear plain full short skirts commonly showing bare feet below. Their waists are seldom visible being concealed by one of two shawls. That these people are generally dirty looking is not strange, since they sleep on the floor and wear he same garments day and night for an indefinite period. It is early to be wondered at that the Aymará Indians are a rather surly looking lot, since they have been robbed of their lands and their more sympathetic rulers, ad made subject to an alien race by whom in earlier days thy were ill-treated and oppressed far more than now. Yet as a rule they are peaceable and quiet except in the rare periods of insurrection when their latent savager is liable to break forth (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 62).

“The Brysons kindly supplied animals to Cajabamba, with a note directing their major demo there to send me on to San Jacinto. He was a lazy inefficient individual, more interested in airing his little knowledge of English or trying to learn new phrases from me than in speeding me on my way. If I had not urgently insisted, rising early myself, and with shouts and knocks routed him out of bed, I should not have gotten away the next morning. The man who accompanied me downward was indifferent and the baggage mules were tired. They were not the ones designated by Mr. Bryson for the journey as they had come up only the night before with the mails; but it had been too much trouble for the major demo to bring in fresh animals. Soon after leaving Hornillos, still several hours from our destination, one of the mules lay down, causing me much alarm for the safety of my baggage, and anxiety lest the animals should utterly give out or be permanently injured from over-exertion. Yet we could only press onward. Two hours later near the village of Moro, the animal lay down again. By this time the man realized the importance of keeping the mules going, and by continual beating hurried them along until about seven we at last reached the town house of the Gadéas. With difficulty, this man absolutely refusing to go farther, I procured local assistance for the ten miles to San Jacinto the next morning, when a nice boy, of twelve or fourteen who accompanied me greatly surprised me by refusing any money for his trouble” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 262).

“After a few months at Panama, Mr. Smith was tempted to take part in some railway construction on the west coast of Columbia. Much bitter feeling was here manifest on the part of the residents against the two men from the United States, a natural if not logical result of the violent separation of Panama from its mother country. The natives were always saying that as the Americans stole Panama, they had a right to steal from them. One night the Americans’ residence was attacked, but with his handy Winchester, the Superintendent of the Road killed three men, when the rest fled” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 309).

Because of Peck’s education and career lecturing abroad in Europe, she built many connections with wealthy elites all over the world. Due to her unique position as a woman in the mountaineering industry, she also got to know many government officials abroad, such as the ambassador and president of Peru. These relationships partially informed her opinions of the country’s political standings. Additionally, she spent ample time in her reflections discussing the capitalist agenda that she thought should be furthered in South America.

“With a deepening interest in South American countries and peoples, I have been inspired to hope that by drawing attention to the magnificent scenery of the Andes and to other matters observed in my travels, I might augment the awakening interest in our sister Republics beyond the Equator, thus helping to promote travel, commerce, and trade between the two sections, and the construction of the Pan-American Railway. To aid in a small degree the cause of Peace by increasing our knowledge of countries with which we have too little acquaintance, a bond of sympathy and union taking the place of crass conceit and narrow prejudice, has seemed to me even more worth while than the slight contribution I hoped to make to the world’s scientific knowledge” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. xi).

“[We had] a delightful ride up the valley along the paved highway wide enough for carts, but no carts were there. This seems strange in a fertile and thickly settled strict, called the most densely inhabited portion of Peru, a centre, it is said, of a population of several hundred thousand people, most of whom live on the floor or sides of the valley, others in adjoining tributary sections. It had not appeared remarkable that there should be no wagon road over that great mountain range along the sides of those steep cañons, but that no carts, carriages, or wagons were going up and down this populous valley, one hundred miles long, seemed evidence of a lack of energy and enterprise” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 175).

“Spending one night at the sugar plantation and one at Samanco I embarked Monday, August 27, on the steamer, which seemed a good deal like home; the more as I met on board an American, Mr. Thomas F. Sedgwick, a graduate of the University of California, who, after much practical experience in Hawaii and Peru, was filling the position of organiser and Director of the Sugar Experiment Station in Lima connected with the School of Agriculture. From him I received much valuable information in regard to the sugar industry” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 263).

“The traveller who prefers to be in advance of the throng, the investor who would wisely improve the opportunity will not await the consumption of these enterprises. The pleasure seeker may now enjoy a unique and delightful journey: the business man who takes advantage of the present moment will be prepared for the rapid development destined soon to astonish the world. The twentieth century may witness int eh southern half of our continent a more extraordinary material advancement than the nineteenth has seen in the northern. Pery affords a temperate climate even at sea level in the torrid zone. Matchless and varied scenery, admirable remains of antiquity, cities the more interesting since unlike our own, people with charming courtesy and culture, will there be found. Untraversed region await the explorer; minerals of every variety (including vanadium, graphite, tungsten in wolframite, etc.), in rare profusion allure those eager for speedy wealth; sugar and cotton crops of unexampled opulence with all the richest products of tropical and temperate zones invite the settler to unoccupied land. Immigration and capital will not be wanting when the wonderful resources of this great country are recognized and rendered accessible” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 367).

“It was in May, 1909, that one of those distressing episodes occurred, which have given to the Latin-American Republics a reputation for unstable governments, though this, happily, did not results in revolution. A hundred or more armed adherents of a factions, Piérola, making at the noon tide hour a simultaneous attack upon the three entrances of the palace, overpowered the guard, killing many, and proceeded to the Presidential suite. Shooting down his Secretary, they forcibly carried the President to the street, then, surrounded by horsemen, from on place to another, finally to the Plaza de l’Inquisición. With a revolved at his head the demand was made that the President should sign his resignation, which, with great fortitude, he resolutely refused to do” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 369).

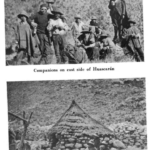

“Very cheerfully, though half dead with the fatigue of hasty preparation, on the 16th of June, 1903, I embarked at New York on the good ship Segurança (italics) in quest of a goal which for five years I had been hoping to attain. With the companionship of a stalwart scientific man, who I believed would prove in eery way a valuable assistant, and of two Swiss guides, one of who was familiar with the country and the mountain we proposed to visit, I felt highly sanguine as to the result; especially as hitherto I had always been favored of fortune and my every undertaking of importance had been crowned with success…I sailed towards what I hoped would prove the utmost height of my ambition (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 7).

Image: Frederic Edwin Church, Heart of the Andes, 1859.

Places Visited

When Peck discussed New York in her writings, it was often for the purpose of comparing the cities she visited in South America to America, whether it be referencing commodity prices or infrastructure development. Although she also mentioned having no home to return to several times, she spent much of her time in America in New York and established several connections with publishing companies and newspapers during her time there who would then write about her expeditions.

“The most feasible project seemed to be the ascent of Orizaba in Mexico, its summit the highest point which had been reached in North America. This became under the auspices of the New York World, in 1897, the easy goal of my ambition and gave me temporarily the world’s record for women” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. x).

“As we have “clean” papers and no illness on board we still hope to catch the Tuesday steamer from Colon to New York, but Monday afternoon are informed that we must do five days’ quarantine. Great but futile is our wrath!” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 118).

“The nearer we came to New York the more unhappy I felt. Although some scientific observations had been made by the expedition, which I hoped might prove of interest and value, to return ignominiously to my native land without having set foot upon the mountain for the ascent of which I had so long planned, had made so elaborate preparations, had spent so much money in procuring supposedly necessary and valuable assistance, and had travelled ten thousand miles, was sufficiently mortifying to make me really ill. A few days after my arrival I had an attack of the shingles, the result, said my physician, of nervous exhaustion…By way of consolation a friend one day remarked, “You wouldn’t have been able to give any lectures if you had climbed the mountain,” to which I indignantly rejoined, “Indeed I should! I should’ never have had the shingles if I had climbed the mountain!” As subsequent events have made obvious” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 121).

“The next night, June 16, I took the steamer for New York; Friday I called on the editor of the Times and found that he really would subscribe for a series of articles. I had made an effort to form a syndicate of newspapers, but editors with one accord replied (if at all) that they were not interested in South America (or presumably in mountain climbing). Only the Boston Herald had promptly responded and even proffered the cash. With the Times in addition and the subscriptions from Rhode Island friends I had about twelve hundred dollars with which to make the venture” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 123).

“In conversation one day he chanced to inquire, ‘Where is your home?’ ‘Where my trunk is,’ I replied. ‘No,’ he said, ‘but where is your real home?’ ‘Where my trunk is,’ I reiterated. ‘Just now here, presently in New York. That is all the home I have.’” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 202).

“The perils of city life especially in New York I have long deemed graver than those of mountain climbing” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 370).

In her books, Peck did not write about the local people in a nuanced of respectful way, and this is particularly apparent in the account of her exploration of Panama. She paid ample attention to the elites in the country, with whom she was interacting or staying with, and much less to other citizens. When she did discuss locals, it was in a rather dehumanized tone.

“Of course, I heard about the old lady who used to go sailing up and down the coast. She was the happy owner of an island in the bay of Panama on which there was a fine spring of water. This was desired by the Pacific Steam Navigation Company, as the water of Panama was not of the best quality” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 117).

“We were fortunate in having passed three of our five days without expense on the Mapocho; the fee on the Medellin was $2.50 a day. Our release came on Thursday with the arrival of a boat to carry us to La Boca” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 119).

“Thursday evening, June 30, there was a little excitement at the hotel in the form of a banquet given by President Amador to the members of the Congress of the Panama Republic in return for one tenered by them to him not long before. Representatives of the French and United States Governments were also in attendance” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 128).

“After a few months at Panama, Mr. Smith was tempted to take part in some railway construction on the west coast of Colombia. Much bitter feeling was here manifest on the part of the residents against the two men from the United States, a natural if not logical result of the violent separation of Panama from its mother country. The natives were always saying that as the Americans stole Panama, they had a right to steal from them. One night the Americans’ residence was attacked but with his handy Winchester, the Superintendent of the Road killed three men, when the rest fled” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 309).

Peck did not spend as much time in the towns of Bolivia as in other countries in South America. Similar to her comments about New York, she mentions Bolivia often in conjunction with Peru or Panama as a way to compare South America. In doing so, her writings often did not acknowledge each countries’ unique properties that differentiated it from those nearby. Bolivia is where she successfully summited Mt. Illampu and “observed,” though did not stay with, Indigenous people and their homes while she awaited a weather window to climb.

“Mr. Sheppard, an Englishman, superintendent of the new railway and Subdirector of Public Works, gave me much valuable information in regard to Bolivia, besides showing other kindnesses” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 31).

“As previously remarked, Bolivia is a peculiar country in mroe ways than one. There are practically no trees of natural growth on the great plateau or elsewhere, save in a few cañons, until you pass over to the east side of the Andes where the owner slopes are thickly wooded” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 65).

“The railway from Guaquil on Lake Titicaca thus completed to La Paz has been of the greatest benefit to Bolivia by facilitating communication with the coast, which, however, still remains expensive, so that the old method of transport by llamas and other pack animals from La Paz to the seaport Arica, much nearer than Mollendo, is still employed for many kinds of freight” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 361).

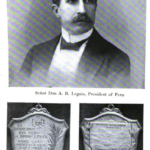

Peru is where Peck spent a lot of time traveling, particularly during her summit attempts of Mt. Huascáran. She was also honored for successfully reaching Mt. Illampu’s summit by the President of the time in Lima, Peru.

“I went over on the afternoon train to Cerro, where I was entertained for two days at the Esperanza, the new office building of the Cerro de Pasco Mining Company. The place is of exceptional interest as the highest large mining camp and the highest considerable town in the world: furthermore because the great copper property is owned by a small number of well-known American millionaires” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 270).

“As from either end we approach the central portion of the Pan American Railway the breaks become larger and larger. North of the 500 mile gap between Cuzco and Huancayo the line is in operation for 150 miles to Oroya, Cerro de Pasco, and Goyllarisquisga…Lines equally necessary, tapping or crossing the longitudinal, are already being arranged for…Another, for which a concession has been granted to an American, Alfred W. McCune, will extend from Goyllarisquisga, a distance of 275 miles to Puca Alpa, a port on the Ucayali, which four months in the year permits the approach of ocean steamers, at all times of ordinary river craft, and gives connection with a network of 4,000 miles of navigable rivers. By means of this railway an extensive region will be brought fifteen or twenty days nearer to New York and Europe than by the more obvious route down the Amazon past Pará. This most favorable concession includes immense grants of land of incalculable wealth in mineral deposits, timber, virgin rubber, and various other agricultural products, while the passing of the road by Yanahuanca, Huánuco, and several other towns ensures traffic from the outset” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 365).

“President Leguia, who had opened his administration with acts for the conciliation of all factions to receive this reward for his generosity, was fortunately preserved to continue his pacific policy towards the neighbouring nations of Bolivia and Ecuador. His name should be known and honoured and his services to the cause of Peace recognised, not only in South America, but throughout the whole civilised world” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 369).

“An agreeable occasion was on the 23rd of November, 1908, when I had the distinction of being the first woman to address in their own language The Lima Geographical Society, my subject, The Conquest of Huascarán, illustrated by stereopticon views” (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 369).

“By no means regarding myself as an independent climber, I should, at the outset, never have dreamed of venturing upon great glaciers without expert professional assistance. Desperation only at length drove me to do" (A Search for the Apex of America, p. 4).

Image: Frederic Edwin Church, View of Cotopaxi, 1867.