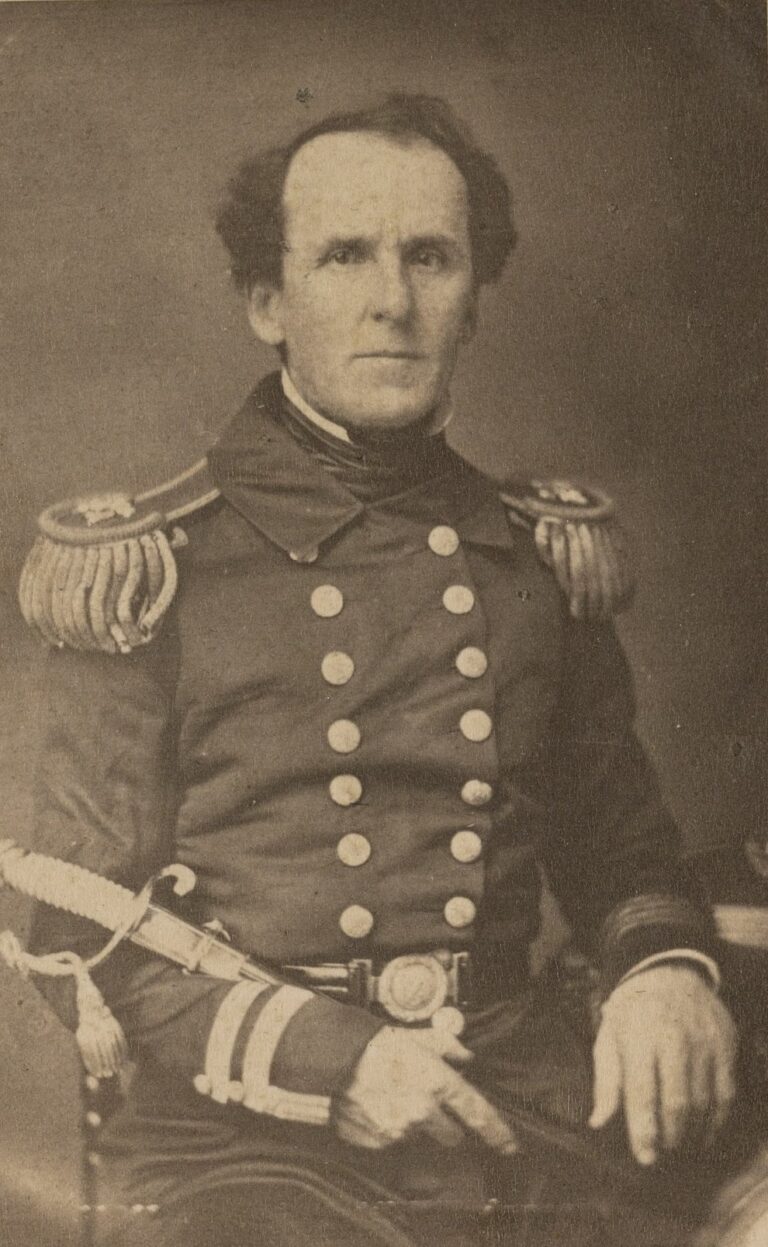

William F. Lynch

Born in Norfolk Virginia on April 1st 1801, William F. Lynch was a religious naval officer serving under the United States Navy and, later, the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. From November 1847 to December 1848, Lynch embarked on a journey to the River Jordan, the Dead Sea and its surrounding territories, including Turkey and Jerusalem, and compiled his observations into his travel journal, Narrative of the United States’ Expedition to the River Jordan and the Dead Sea.

Themes

Gender was a crucial social identifier that had a large impact on the way one was perceived and the expectations society had for them in the nineteenth century. During his expedition, Lynch paid great attention to Middle Eastern women, especially in regards to their features and their dress. He was constantly intrigued by the modest nature of Muslim women and seemed to fetishize the figures and features of these women.

“We did not anticipate seeing so many Turkish females in the streets. It seems that, like many of their sex in our own country, they spend a great deal of their time in shopping.” (chapter IV)

“Christianity has ever expressed the deepest solicitude for the female; for the inordinate authority of man over woman, or the undue subjection of the female to the male, tends to the debasement of the morals of each. Woman, even when invested with the plenitude of her rights and mistress of her own actions, is but too often the feeble victim of the seducements which surround her. How utterly helpless is she, therefore, when her will is not her own. The very idea of resistance vanishes, vice becomes a seeming duty, and man, gradually debased by the facility with which his irregular appetites are indulged, plunges into the lowest depths of sensuality. Woman, whose influence over the heart of man is irresistible, whenever she is debased, revisits her corruption upon man; and thus this pervading influence of the sexes over each other, by a species of mutual contamination, moves from generation to generation in one vicious circle, from which they can only be delivered by the supernatural and refining influence of Christianity” (Chapter IV)

“There was, on an adjoining terrace, a young girl with a glorious profusion of curling tresses, which, from beneath a golden net-work on her head, fell gracefully down upon her dumpy form. Besides a boddice, or spencer, she wore a short pelisse and full trousers, which, to say the least, were rather the worse for wear. I should have admired the dark, wild-looking eye and the luxuriant hair, had it not been whispered to me that in the morning her beautiful head was seen undergoing a more critical examination than would be necessary with one of our fair countrywomen.” (Chapter VI)

“She was timid, yet dignified in her manners; the wave of her hand was particularly graceful, and her voice soft and gentle, — “an excellent thing in woman.”” (Chapter XXI)

“All over the world, civilized and savage, women are treated as inferior beings. In what is esteemed refined society, we hold them in mental thraldom, while we exempt them from bodily labour; and, paying a sensual worship to their persons, treat them as pretty playthings.” (Chapter XXI)

Race was another crucial social identifier in the ninteenth century, especially to Americans that were dealing with the discourse regarding slavery and the status of Black people in the United States. Therefore, race played a large role in Lynch’s observations that were tinged with his inherent racist beliefs and biases as well as his general belief in white superiority.

“Just within the Spanish barrier is a small village, containing fifty or sixty houses, a few constructed of stone, but most of them of thatched straw. What a contrast it presents to the cleanliness, order, and air of comfort which pervade the fortress, so short a distance from it! Ill clad, lazy men, lounging in the sun; homely, dirty, dishevelled women, with yet filthier children, seated in the door-ways; and hordes of importunate beggars, who, the dogs excepted, are the only active inhabitants of the place, all too plainly bespeak an unhappy and misgoverned country.” (Chapter II)

“We were surrounded by a crowd of curious Arabs, of all ages and conditions, — their costumes picturesque and dirty. The rabble already began to show their thievish propensities by stealing the little copper chains of our thole-pins. They thought that they were gold.” (Chapter VI)

“The Emir and some of his people have wiry hair and very dark complexions, but no other feature of the African. His brother and some of the tribe are bright, but less so than ’Akil and his followers. The darker colour of the skin may, perhaps, be attributed to the climate of the Ghor.” (Chapter X)

“We have not seen an instance of deformity among the Arab tribes. This man was magnificently formed, and when he walked it was with the port and presence of a king. It has been remarked that races with highly coloured skins are rarely deformed; and the exemption is attributed, perhaps erroneously, not to a mode of life differing from that of a civilized one, but to hereditary organization.” (Chapter XIV)

As a Christian himself, Lynch had a skewed perception of the other religions he encountered on his journey. This is made clear during his commentary regarding Muslims and Jews. However, since Christianity was in the minority in the Middle East, Lynch also faced some prejudices due to his beliefs.

“Civilization has scarce landed upon these shores; and in Syria, we may look for more unadulterated specimens of the Muslim character than in the capital of the empire.” (Chapter VI)

“I scarce realized my position. Could it be, that with my companions I had been permitted to explore that wondrous sea, which an angry God threw as a mantle over the cities he had condemned, and of which it had been heretofore predicted that no one could traverse it and live. It was so, for there, far below, through the descending vista, lay the sombre sea. Before me, on its lofty hill, four thousand feet above that sea, was the queenly city. I cannot coincide with most travelers in decrying its position. To my unlettered mind, its site, from that view, seemed, in isolated grandeur, to be in admirable keeping with the sublimity of its associations. A lofty mountain, sloping to the south, and precipitous on the east and west, has a yawning natural fosse on those three sides, worn by the torrents of ages. The deep vale of the son of Hinnom; the profound chasm of the valley of Jehoshaphat, unite at the south-east angle of the base to form the Wady en Nar, the ravine of fire, down which, in the rainy season, the Bidron precipitates its swollen flood into the sea below.” (Chapter XX)

“It needs but the destruction of that power which, for so many centuries, has rested like an incubus upon the eastern world, to ensure the restoration of the Jews to Palestine. The increase of toleration; the assimilation of creeds; the unanimity with which all works of charity are undertaken, prove, to the observing mind, that, ere long, with every other vestige of bigotry, the prejudices against this unhappy race will be obliterated by a noble and a God-like sympathy. “Many a Thor, with all his eddas, must first be swept into dimness;” — but the time will come. All things are onward; and, in God’s providence, all things are good. How eventful, yet how fearful, is the history of this people! “The Almighty, moved by their lamentations, determined, not only to relieve them from Egyptian bondage, but to make them the chosen depositary of his law, by the observance of which men might be gradually prepared for the advent of the Saviour. Living at first under a theocracy, the most perfect form of government that can exist, for it unites infinite wisdom with power supreme;” and subsequently, under judges, prophets, and kings, the Israelites were led through wondrous vicissitudes to the trying scene, which crowned their perfidy with an act so atrocious that, like the glimmer of an earthly torch before the lurid glare of pandemonium, their previous crimes sunk into insignificance; and nature thrilled with horror as she looked upon the deicides, their hands imbrued in the blood they should have worshipped. Yet even this sin will be forgiven them; and the fulfilment of the prophecy with regard to the Egyptians ensures the accomplishment of the numerous ones which predict the restoration of the tribes. Besides overwhelming Pharaoh and his host, the Almighty decreed, through Ezekiel, that Egypt should never obey a native sceptre. From Cambyses to the Mamelukes; from Muhammed to Ali Pasha, how wonderfully has this judgment been carried out!” (Chapter XXI)

“The Jewesses, while they enveloped their figures in loose and uncomely robes, allowed their faces to be seen; and the Christian and the Turkish female exhibited, the one, perhaps, too much, the other, nothing whatever of her person and attire.” (Chapter XXI)

“While making our way through a crowded bazaar, a Turk, in passing, elevated his hands above his head. We did not at the time understand it, but learned afterwards, that formerly it was an enforced custom for Christians to keep the centre of the street, which is nothing more than a gutter, while the Muslims passed along the elevated side-walk. The Turk, on this occasion, not being so tall as the member of our party next to him, his gesture was intended as a kind of assertion of superiority.” (Chapter XXV)

Since Lynch was from the United States, he was intrigued by the customs of the Middle East. Not only does he describe these foreign practices, but he also inserts his own commentary on Middle Eastern laws, customs and moral reasonings.

“By a law of the Ottoman Empire, no one within its limits can be held in slavery for a period exceeding seven years” (Chapter IV)

“In Turkey, every coloured person employed by the government receives monthly wages; and if a slave, is emancipated at the expiration of seven years, when he becomes eligible to any office beneath the sovereignty. Many of the high dignitaries of the empire were originally slaves; the present Governor of the Dardanelles is a black, and was, a short time since, freed from servitude. There is here no prejudice founded on distinction of colour. The avenues of preferment are open to all, and he who is most skilful, accomplished and persevering, be his complexion ruddy, brown or black, is most certain of success.” (Chapter IV)

“The customs of the east and of the west are singularly blended, but the races remain distinct, separated by difference of complexion and of faith.” (Chapter VI)

“From all the information I could procure of the Arab character, I had arrived at the conclusion, that it would tend more to gain their good-will if we threw ourselves among them without an escort, than if we were accompanied by a strong armed force. In my first interview with Sa’id Bey, therefore, I only asked for ten horsemen, to act as videttes, which, under the impression that they would be insufficient, he so long hesitated to grant, that I withdrew the application, and resolved to proceed without them. He afterwards pressed me to take them, and, calling upon me at the consul’s, offered to furnish them free of cost; but I was steadfast in refusal. The attack upon our countrymen, however, indicated danger of collision at the very outset, and I determined to be prepared for it. On leaving the Supply, I had placed a sum of money in charge of Lieutenant-Commanding Pennock, with the request, that he would, in person, deliver it to H.B.M. Consul at Jerusalem. Partly for that purpose, and in part to make some simultaneous barometrical observations, he had sailed for Jaffa, which is about thirty miles distant from the Holy City. To him, therefore, I despatched a messenger, asking him to call upon the Pasha, and request a small body of soldiers to be sent to meet us at Tiberias, or on the Jordan. This precaution taken, my mind was at ease, and, indeed, I was half ashamed of the previous misgivings; for, from the first, I had felt that we should succeed.” (Chapter VI)

“There were some fellahas (female fellahin) on a plain to the northward of us. They allowed Mustafa to approach within speaking distance, but no nearer. They asked who we were, how and why we came, and why we did not go away. About an hour after, some thirty or forty fellahin, the sheikh armed with a sword, the rest with indifferent guns, lances, clubs, and branches of trees, came towards us, singing the song of their tribe. I drew our party up, the blunderbuss in front, and, with the interpreter, advanced to meet them. When they came near, I drew a line upon the ground, and told them that if they passed it they would be fired upon. Thereupon, they squatted down, to hold a palaver. They belonged to the Ghaurariyeh, and were as ragged, filthy, and physically weak, as the tribe of Rashayideh, on the western shore. Finding us too strong for a demand, they began to beg for backshish. We gave them some food to eat, for they looked famished; also a little tobacco and a small gratuity, to bear a letter to ’Akil , (who must soon be in Kerak,) appointing when and where to have a look-out for us.” (Chapter XIV)

“After embarking the boats, and making all necessary arrangements for to-morrow’s start, among them, procuring quantities of every variety of seed, we returned to our quarters, to spend the last night in the spacious but infested villa of our most worthy consul. Great was our surprise, and unequalled our delight, when, shortly after, the younger Sherîf came in and explained the cause of his reserved demeanour in the morning. A valuable slave had absconded from him at Acre, taking with him his master’s best horse and a highly prized rifle. Following in swift pursuit, Musaid had tracked him to Jaffa, and was, incognito, making some necessary inquiries, when we suddenly came upon him. He ascertained that the slave had continued his flight to Egypt, and purposed following in pursuit. In reply to our inquiries, Sherîf humanely said that if he came within gun-shot of the fugitive, he would not shoot him, even to secure his horse and his gun. He expressed his regret that he had not parted with the slave some time before, when he seemed dissatisfied. By an imperial edict (which is, however, disregarded with respect to Nubians), a slave cannot remain in servitude more than seven years; and, by a custom, the most imperative of all laws, a slave, if dissatisfied, can claim to be sold; and if the demand be thrice ineffectually made, before witnesses, he becomes, ipso facto, free. Hence, the treatment of slaves is mild and conciliatory.” (Chapter XXII)

Lynch made many observations about the physical environment and climate around him as he journeyed through the Middle East, describing the flora and fauna, foreign species of animals, rock formations as well as the sea conditions he encountered.

“For hours in their swift descent the boats floated down in silence, the silence of the wilderness. Here and there were spots of solemn beauty. The numerous birds sang with a music strange and manifold; the willow branches were spread upon the stream like tresses, and creeping mosses and clambering weeds, with a multitude of white and silvery little flowers, looked out from among them; and the cliff swallow wheeled over the falls, or went at his own wild will darting through the arched vistas, shadowed and shaped by the meeting foliage on the banks; and, above all, yet attuned to all, was the music of the river, gushing with a sound like that of shawms and cymbals.” (Chapter X)

“We here gathered a few flowers, which, the offspring of a more mature season, were gaudy in their colouring, but less redolent of fragrance, than those which bloomed around us on our previous visit. From the heat of the climate, vegetation germinates, matures, decays, and revivifies, with great rapidity.” (Chapter XXIII)

“We this day paid particular attention to the geological construction of the western shore, with a special regard to the disposition of the ancient terraces and abutments of the tertiary limestone and marls. There may be rich ores in these barren rocks. Nature is ever provident in her liberality, and when she denies fertility of surface, often repays man with her embowelled treasures. There is scarce a variety of rock that has not been found to contain metals; and it is said that the richness of the veins is for the most part independent of the nature of the beds they intersect.” (Chapter XIV)

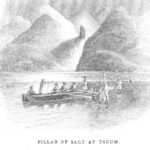

“The beach was a soft, slimy mud encrusted with salt, and a short distance from the water, covered with saline fragments and flakes of bitumen. We found the pillar to be of solid salt, capped with carbonate of lime, cylindrical in front and pyramidal behind. The upper or rounded part is about forty feet high, resting on a kind of oval pedestal, from forty to sixty feet above the level of the sea. It slightly decreases in size upwards, crumbles at the top, and is one entire mass of crystallization. A prop, or buttress, connects it with the mountain behind, and the whole is covered with debris of a light stone colour. Its peculiar shape is doubtless attributable to the action of the winter rains. The Arabs had told us in vague terms that there was to be found a pillar somewhere upon the shores of the sea; but their statements in all other respects had proved so unsatisfactory, that we could place no reliance upon them.” (Chapter XIV)

“For miles the way was lined with walls composed of sun-dried blocks of mud, intermixed with pebbles, each about three feet high, four feet long; and one foot thick, larger, but in every other respect very much like the adobes of Mexico. This climate is said to be very cold in winter. It can only be so by contrast with the heat of summer, for much frost would crumble these walls in a single season. Within the lines of walnut trees there were orchards of olives and apricots, and patches of wheat, barley, melons, and leguminous plants. The road ran winding among these delicious gardens, with a rapid stream always on one and generally on both sides, and to which, through each garden there flowed a brawling tributary.” (Chapter XXV)

“The country was highly cultivated, with barley, dhoura, the walnut (which is an article of food), the olive, fig, apricot, and mulberry, the pea, and the castor bean. As we advanced, the olive was succeeded by the mulberry and the vine. The rocks were limestone, conglomerate, quartz, and concretions, and in one place there were scattered fragments of marble columns on the plain; and just below a Roman bridge a thick stratum of incrustations of roots of trees and other vegetable matter. The prevailing flowers were the wild white rose; a vine resembling the morning-glory, and a beautiful pink flower. It is strange that with a climate so similar to this, South America does not produce the white rose.” (Chapter XXV)

“Many writers have undertaken to describe the first sight of Jerusalem; but all that I have read convey but a faint idea of the reality. There is a gloomy grandeur in the scene which language cannot paint. My feeble pen is wholly unworthy of the effort. With fervent emotions I have made the attempt, but congealed in the process of transmission, the most glowing thoughts are turned to icicles."

Image:Jerusalem Mount Zion in 1840, https://pixels.com/featured/jerusalem-mount-zion-in-1840-munir-alawi.html

Places Visited

The Spanish jurisdiction of Gibraltar and Port Mahon were the first destinations Lynch had arrived at after his departure from the Brooklyn Naval Yard and made many observations about their physical environments. These places also exposed Lynch to his first encounter with the “other” and revealed his inherent racist beliefs and feelings of white superiority.

“In a few hours the low lands were sunk beneath the horizon, and at sunset the high lands of “Navesink” were alone visible above the agitated surface of the water. The dry wind sweeping over the land, which had been saturated by the rains of the two preceding days, caused an evaporation so great as wonderfully to increase the refraction. The setting sun, expanding as it dipped, and varying its hues with its expansion, assumed forms as unique as they were beautiful. Now elongated in its shape, and now flattened at its ends, it would, at times, be disparted by the white crest of an intervening wave, and present alternately the appearance of golden cups and balls, and jeweled censers tossing about upon a silver sea. As the minutes advanced, the western sky, tint by tint, became one glorious suffusion of crimson and orange, and the disc of the sun, flattening, widening, and becoming more ruddy and glowing as it descended, sunk at last, like a globe of ruby in a sea of flame.”

“The rock of Gibraltar, abrupt on this, its western side, and on the other absolutely precipitous, has a summit line, sharp and rugged, terminating with a sheer descent on its northern face, and sloping gradually to Europa point at its south extreme. From an angle of the bay, this rock, 1400 feet high and three miles long, presents the exact appearance of a couchant lion; — his fore-paws gathered beneath him, his massive, shaggy head towards Spain, his fretted mane bristling against the sky, and his long and sweeping tail resting upon the sea.”

“Mahon, so named from Mago, the brother of Hannibal, is the chief town of the island of Minorca. It is beautifully situated at the northwest extremity of one of the most secure and spacious harbours in the world. This port, since the first introduction of a U. S. naval force in the Mediterranean, subsequent to the war with the free-booters of Barbary, has, with few exceptions, been the winter rendezvous of our squadrons stationed in that sea. Why it should be so, with the security of the anchorage its only recommendation, it is difficult to conceive. Other places there are, sufficiently secure, less isolated in their position, less tempestuous in their winter climate, abounding with classical associations and teeming with inducements to scientific research, far superior to Port Mahon. A place famed for the facilities it presents for acquiring, and the cheapness of indulging low and vicious habits: — famed for the circumstance that the senior officers, and all who can be spared from watch, abandon their ships and reside for months on shore; while many of the young and the inexperienced, and some of their superiors, spend much of their time and all their money in the haunts of the dissipated and the vile. I do not mean to reflect upon the respectable part of the population of Mahon, for there is not a more kind-hearted or gentle people in the world. But ignorance of the language compels most of our officers to keep aloof from a society, which, if it do not increase the refinement of their manners, should at least protect them from moral degradation.”

“Apart from all moral considerations, there are political ones why Port Mahon should not be the winter rendezvous of our squadron in the Mediterranean. Within twelve years, difficulties were once anticipated with France, and twice with England; — with the former power on the subject of indemnity, and with the latter on the questions of the north-eastern boundary and the disputed claim to Oregon. On these occasions, our depot was, and our squadrons mostly were, at this port, in a small island, two hundred miles distant from Toulon, the nearest point on the main land, and equi-distant from Gibraltar and Malta — all three strongholds of probable enemies. Its isolated position debars intelligence from the continent more frequently than once a month, and the first indication of hostilities might have been the summons of a hostile fleet. It is true that our commanders have received directions not to winter at Mahon, but orders are fruitless while commanders of squadrons claim the privilege of exercising their own judgment without regard to the instructions of the authorities at home. We found the flag-ship here, and here it is believed that the squadron will winter.”

During Lynch’s time in Smyrna, Greece, Lynch focused on three main themes, Turkish women, Oriental scenes and architecture as well as his thoughts on the punishment of crime in Smyrna.

“The city of Smyrna, so inviting in its exterior, is crowded, dirty, and unprepossessing within. The houses, excepting those on the Marina, or Water front, rarely exceed one story in height, and are dingy and mean; and the very mosques, so imposing from without, fall far short of the conceptions of the visitant. The Smyrniotes have fair complexions, much fairer, we think, than the people of the Morea, and very much more so than the Kurds, Armenians, Syrians, and Jews.”

“We alighted before an elegant villa, and entering a porte-cochere, passed along an avenue bordered with fragrant shrubs and a variety of flowers, with orange-groves on each side, and up a lofty flight of steps into the main building, which was beautifully furnished in the European style. After a while, we were conducted through the garden, upon walks of variegated pebbles, set in diamond figures. We were thence led to a small kiosk, or summer house, where pipes were brought by female servants of decided Grecian features. A queen-like old lady, dressed in a blue silk sack, trimmed with rich fur, and wearing upon her head a braided turban interwreathed with natural flowers and silver ornaments, was introduced to us by our kind entertainer as his mother. Presently, a silver salver was brought, with small dishes of the same material upon it, containing conserves of various kinds. Taking it from the servant, the superb old lady handed it to each of us in turn, not omitting her son. This is one of the customs of the East which so peculiarly differ from our own. Here man is indeed the sole monarch of creation; but his degradation of the female sex recoils fearfully upon himself.”

In Constantinople, Lynch visited a cotton farm in San Stefano, embarked on a short excursion on the Bosphorus and travelled to the Tomb of Joshua, a burial site of the biblical figure Joshua. From his experiences, Lynch shared his contradictory opinions on slavery as well as explained the system of slavery within Constantinople.

“The town of Dardanelles (Abydos), situated on the Asiatic side, is unattractive in its appearance, but a mart of considerable commerce. A number of consular flags wave along the water-front, and here, vessels bound to Constantinople, or to any of the ports of the Euxine, must await their firman or permit. The castles of the Dardanelles are formidable — the one on the Asiatic side especially so, from its heavy water-battery.”

“The farm consists of about two thousand acres of land, especially appropriated to the culture of the cotton-plant. Both farm and school are under the superintendence of Dr. Davis, of South Carolina; a gentleman who, in the estimation of Armenians, Turks and Franks, is admirably qualified for his position. He is intelligent, sustains a high character, and has many years’ experience in this branch of cultivation. Already he has made the comparatively acid fields to bloom; and besides the principal culture, is sedulously engaged in the introduction of seeds, plants, domestic animals, and agricultural instruments. The school is held in one of the kiosks of the sultan, which overlooks the sea.”

“In Turkey, every coloured person employed by the government receives monthly wages; and if a slave, is emancipated at the expiration of seven years, when he becomes eligible to any office beneath the sovereignty. Many of the high dignitaries of the empire were originally slaves; the present Governor of the Dardanelles is a black, and was, a short time since, freed from servitude. There is here no prejudice founded on distinction of colour. The avenues of preferment are open to all, and he who is most skilful, accomplished and persevering, be his complexion ruddy, brown or black, is most certain of success.”

“We embarked with our minister, Mr. Carr, in his sixteen-oared caique, for a trip up the Bosporus. The lovely and meandering Bosporus, ever at the ebb, but rarely turbulent, for the last five miles before it becomes merged in the Sea of Marmara, flows between almost uninterrupted ranges of mosques, palaces, gardens, and it was in vain to attempt to describe it. I only noted such prominent places as, from time to time, we passed.”

“The view from this mountain height surpasses all that in my wandering life I have ever seen. The Black Sea, its surface dotted with many sails, stretched in a boundless expanse to the north; nearer were the Symplegades and the mouth of the strait, and nearer yet the Genoese ruin on the site of the temple of Serapis, and over against it the ancient Pharos, or light-house of the strait.”

Lynch and his crew anchored in Beirut and were received by the Pasha, the highest rank in the Ottoman Empire next to the Sultan. Lynch was quick to comment on the racial and cultural makeup of Beirut. As a Franco-Syrian town, Lynch noticed a mix of cultures and customs between the east and west, describing them as “singularly blended”

“Beïrût is a Franco-Syrian town, with a proportionate number of Turkish officials. The customs of the east and of the west are singularly blended, but the races remain distinct, separated by difference of complexion and of faith. The most striking peculiarity of dress we saw, was the tantur, or horn, worn mostly by the wives of the mountaineers. It was from fourteen inches to two feet long, three to four inches wide at the base, and about one inch at the top. It is made of tin, silver, or gold, according to the circumstances of the wearer, and is sometimes studded with precious stones. From the summit depends a veil, which falls upon the breast, and, at will, conceals the features. It is frequently drawn aside, sufficiently to leave one eye exposed, —in that respect resembling the mode of the women of Lima. It is worn only by married women, or by unmarried ones of the highest rank, and once assumed, is borne for life.”

“The road to the convent led for a short distance through an extensive olive orchard, and thence up the mountain by a gentle ascent. On the plain, and the mountain side, were flowers and fragrant shrubs, — the asphodel, the pheasant’s eye, and Egyptian clover. The convent stands on the bold brow of a promontory, the terminus of a mountain range 1200 feet high, bounding the vale of Esdraelon on the south-west. The view from the summit is fine. Beneath is a narrow but luxuriant plain, upon which, it is said, once stood the city of Porphyraea. Sweeping inland, north and south, from Apollonia in one direction to Tyre in another, with Acre in the near perspective, are the hills of Samaria and Galilee, enclosing the lovely vale of Sharon and the great battle-field of nations, the valley of Esdraelon; while to the west lies the broad expanse of the Mediterranean. But the eye of faith viewed a more interesting and impressive sight; for it was here, perhaps upon the very spot where I stood, that Elijah built his altar, and “the fire of the Lord fell and consumed the burnt sacrifice, and the wood and the stones and the dust, and licked up the water that was in the trench.”

Lynch and his men dined with the governor and many other important figures during his stay in St Jean d’Acre. During his interactions with the dinner guests, as well as the people in the town, Lynch continued to reveal his prejudiced thoughts towards Middle Eastern people.

“Thence, the beach sweeps out into a low projecting promontory, on which stands “Akka,” the “St. Jean d’Acre” of the Crusades, and the “Ptolemais” of the New Testament.”

“Had I not been in so much anxiety about our operations, the whole scene upon my entrance into St. Jean d’Acre would have been exceedingly interesting. It is the strangest-looking place in the world, besides its being so renowned from the days of chivalry to the English bombardment.”

“A short distance within the gate was a narrow bazaar, roughly paved, about two hundred yards in length, with small open shops, or booths, on each side. They only exhibited the common necessaries of life for sale. A short distance farther, opposite to the inner wall, was a line of workshops, mostly occupied by shoemakers. These, with a few feluccas in the harbour, presented the only indications of commerce.”

“Late in the afternoon, I received an invitation from Sa’id Bey to come to the palace. Ascending a broad flight of steps, and crossing a large paved court, I was ushered into an oblong apartment, simply furnished, with the divan at the farther end. I was invited to take the corner seat, among Turks the place of honour. Immediately on my right, was the cadi, or judge, a venerable and self-righteous looking old gentleman, in a rich cashmere cloak, trimmed with fur. On his right sat the governor. Around the room were many officers, and there were a number of attendants passing to and fro, bearing pipes and coffee to every new comer. But, what specially attracted my attention, was a magnificent savage, enveloped in a scarlet cloth pelisse, richly embroidered with gold. He was the handsomest, and I soon thought also, the most graceful being I had ever seen. His complexion was of a rich, mellow, indescribable olive tint, and his hair a glossy black; his teeth were regular, and of the whitest ivory; and the glance of his eye was keen at times, but generally soft and lustrous. With the tarbouch upon his head, which he seemed to wear uneasily, he reclined, rather than sat, upon the opposite side of the divan, while his hand played in unconscious familiarity with the hilt of his yataghan.”

Lynch’s writings about his voyage down the River Jordan were shrouded with an air of mysticism and romanticist language. A large portion of the chapters recounting Lynch’s travels through the River Jordan were dedicated to descriptions of the river itself and its water conditions.

“We started at 2 P.M., the temperature of the air 82°, of the water 70°. For the first hour we steered S.E., then S.E. by S., and E.S.E., when, at 3:40, we arrived at the outlet. The same feeling prevented us from cheering as when we launched the boats, although before us was the stream which, God willing, would lead us to our wondrous destination.”

“From the river, the banks sloped gradually to the terrace above; presenting a broad and undulating surface of sparse wild oats and weeds, and a few fields of grass, intermingled with low bushes, and a slender brown fringe of such light and frail structure, as to bend low with the faintest breath of air.”

“The sun went down and night gradually closed in upon us, and the rush of the river seemed more impetuous as the light decreased. We twice passed down rapids, taking care each time to hug the boldest shore. Besides the transition from light to darkness, we had exchanged a heated and stifling for a chilly atmosphere; and while the men, more fortunate, kept their blood in circulation by pulling gently with the oars, the sitters in the stern-sheets fairly shivered with the cold.”

“At 10:15 A.M., cast off and shot down the first rapid, and stopped to examine more closely a desperate-looking cascade of eleven feet. In the middle of the channel was a shoot at an angle of about sixty degrees, with a bold, bluff, threatening rock at its foot, exactly in the passage. It would therefore be necessary to turn almost at a sharp angle in descending, to avoid being dashed to pieces. This rock was on the outer edge of the whirlpool, which, a caldron of foam, swept round and round in circling eddies. Yet below were two fierce rapids, each about 150 yards in length, with the points of black rocks peering above the white and agitated surface. Below them again, within a mile, were two other rapids — longer, but more shelving and less difficult.”

“It was a bright moonlight night; the dew fell heavily, and the air was chilly. But neither the beauty of the night, the wild scene around, the bold hills, between which the river rushed and foamed, a cataract, nor moon-light upon the ruined villages, nor tents pitched upon the shore, watch-fires blazing, and the Arab bard singing sadly to the sound of his rebabeh, could, with all the spirit of romance, keep us long awake. The rebabeh is shaped like a miniature spade, with a short handle; the lowest and widest part, covered with sheepskin on both sides, is about one inch thick and five wide. The ghoss (bow) is simply a bent stick, with horse-hair for strings. This instrument is, perhaps, a coarser specimen of the nokhara khana, which is played before the gateways of palaces in Persia.”

“It was here that Jacob wrestled with the angel, at whose touch the sinew of his thigh shrunk up. In commemoration of that event, the Jews, to this day, carefully exclude that sinew from animals they kill for food. This river, too, marks the northern boundary of the land of the Ammonites.”

Lynch’s writings about the Dead Sea were comparable to that of the River Jordan, however, rather than containing an air of romanticism, his writing had more of a moody and weary quality that reflected the environment of the Dead Sea.

“But, although the sea had assumed a threatening aspect, and the fretted mountains, sharp and incinerated, loomed terrific on either side, and salt and ashes mingled with its sands, and foetid sulphurous springs trickled down its ravines, we did not despair: awe-struck, but not terrified; fearing the worst, yet hoping for the best, we prepared to spend a dreary night upon the dreariest waste we had ever seen.”

“the wind rose so rapidly that the boats could not keep head to wind, and we were obliged to haul the log in. The sea continued to rise with the increasing wind, which gradually freshened to a gale, and presented an agitated surface of foaming brine; the spray, evaporating as it fell, left incrustations of salt upon our clothes, our hands and faces; and while it conveyed a prickly sensation wherever it touched the skin, was, above all, exceedingly painful to the eyes. The boats, heavily, laden, struggled sluggishly at first; but when the wind freshened in its fierceness, from the density of the water, it seemed as if their bows were encountering the sledge-hammers of the Titans, instead of the opposing waves of an angry sea.”

“Towards midnight, while the moon was rising above the eastern mountains, and the shadows of the clouds were reflected wild and fantastically upon the surface of the sombre sea; and everything, the mountains, the sea, the clouds, seemed spectre-like and unnatural, the sound of the convent-bell of Mar Saba struck gratefully upon the ear; for it was the Christian call to prayer, and told of human wants and human sympathies to the wayfarers on the borders of the Sea of Death.”

A military reconnoissance and observations about the the Usdum salt pillar.

“TUESDAY, APRIL 25. Completed a set of observations, bundled up the mess things, and started, at 9:40, for a reconnoissance of the southern part of the sea; leaving Sherîf in charge of the camp, with Read and the four Turkish soldiers. Steered about south, from point to point, keeping near the Arabs along the shore, for their protection; for they dreaded an attack from marauding parties. Threw the patent log overboard; the weather fair but exceedingly hot; thermometer, 89°; little air stirring; no clouds visible; the mountains, as we passed, seemed terraced, but the culture was that of desolation.”

“Seetzen saw this salt mountain in 1806, and says that he never before beheld one so torn and riven; but neither Costigan nor Molyneaux, who were in boats, came farther south on the sea than the peninsula.”

“The beach was a soft, slimy mud encrusted with salt, and a short distance from the water, covered with saline fragments and flakes of bitumen. We found the pillar to be of solid salt, capped with carbonate of lime, cylindrical in front and pyramidal behind. The upper or rounded part is about forty feet high, resting on a kind of oval pedestal, from forty to sixty feet above the level of the sea. It slightly decreases in size upwards, crumbles at the top, and is one entire mass of crystallization. A prop, or buttress, connects it with the mountain behind, and the whole is covered with debris of a light stone colour. Its peculiar shape is doubtless attributable to the action of the winter rains. The Arabs had told us in vague terms that there was to be found a pillar somewhere upon the shores of the sea; but their statements in all other respects had proved so unsatisfactory, that we could place no reliance upon them.”

Lynch’s devotion to Christianity is apparent during his chapter on Jerusalem as much of his writing revolved around religious beliefs, biblical stories and his utter amazement at finally visiting the holy city of Jerusalem. It seemed that in Jerusalem, Lynch felt more connected to Christianity than ever before and it was solidified as a central pillar to his sense of self.

“I rode to the summit of a hill on the left, and beheld the Holy City, on its elevated site at the head of the ravine. With an interest never felt before, I gazed upon the hallowed spot of our redemption. Forgetting myself and all around me, I saw, in vivid fancy, the route traversed eighteen centuries before by the Man of Sorrows. Men may say what they please, but there are moments when the soul, casting aside the artificial trammels of the world, will assert its claim to a celestial origin, and regardless of time and place, of sneers and sarcasms, pay its tribute at the shrine of faith, and weep for the sufferings of its founder.”

“Many writers have undertaken to describe the first sight of Jerusalem; but all that I have read convey but a faint idea of the reality. There is a gloomy grandeur in the scene which language cannot paint. My feeble pen is wholly unworthy of the effort. With fervent emotions I have made the attempt, but congealed in the process of transmission, the most glowing thoughts are turned to icicles. The ravine widened as we approached Jerusalem; fields of yellow grain, orchards of olives and figs, and some apricot-trees, covered all the land in sight capable of cultivation; but not a tree, nor a bush, on the barren hill-sides. The young figs, from the size of a currant to a plum, were shooting from the extremities of the branches, while the leaf-buds were just bursting. Indeed, the fruit of the fig appears before the leaves are formed, [Kitto’s Palestine] and thus, when our Saviour saw a fig-tree in leaf, he had, humanly speaking, reason to expect to find fruit upon it.”

“The city is nearly in the form of a parallelogram, about three-fourths of a mile long, from east to west, and half a mile broad, from north to south. The walls are lofty, protected by an artificial fosse on the north, and the deep ravines of Jehoshaphat, of Gihon, and the Son of Hinnom, on the east, south, and west. There are now but four gates to the city. The Jaffa gate, the fish-gate of the New Testament, on the west; the Damascus gate, opening on the great northern road, along which our Saviour travelled, when, at twelve years of age, he came up with his mother and kindred; the gate of St. Stephen, on the east, near the spot where the first Christian martyr fell, and overlooking the valley of Jehoshaphat; and the Zion gate, to the south, on the crest of the mount. Immediately within the last, are the habitations of the lepers.”

In Jaffa, a city Lynch described as the oldest city in the world and was the site of where Andromeda was chained to a rock in Greek mythology, Lynch dined with the consul and seemed to objectify his wife.

“The town of Jaffa is situated on a hill-side, the declivity towards the sea, and sweeping round it, inland, from north to south, is a plain of luxuriant vegetation, consisting of gardens and orange and mulberry groves, separated by hedges of cactus, fifteen feet high, then in full blossom, bearing a beautiful straw-coloured, cup-shaped, wax-looking flower. The roads, numerous but narrow, and shaded by the magnificent sycamore fig, wind between these hedges, the tenderest leaves of which are cropped by the passing camels, though, from being fretted with thorns, they are avoided by every other animal.”

“The consul’s dinner was an extremely plentiful one, consisting of a great variety of dishes, many of them unknown to us, prepared in the Eastern style. His wife, in compliment to us, for the first time in her life, sat down to a table with strangers. She had a sweet countenance, and her profile was a beautiful one. She was timid, yet dignified in her manners; the wave of her hand was particularly graceful, and her voice soft and gentle, — “an excellent thing in woman.” She was dressed richly, according to the fashion of her country. Her head was ornamented with diamonds, in clusters of leaves and flowers; and on her finger was a magnificent ruby, encircled with brilliants. When she turned to address those who were waiting behind her, we were particularly struck with the exquisite contour and flexure of her head and throat. A master-artist would have painted her so, and called her the heroine of some historic scene. From time to time, she helped us to morsels from her own plate; a marked compliment, founded on a custom which, under other circumstances, we should have thought “more honoured in the breach than the observance;” but her manner was so gentle and so winning, and her smile so irresistible, that, had it been physic instead of palatable food, we should have swallowed it without hesitation.”

“In the afternoon there was a marriage-procession; the bride being escorted to her future home by her husband and his friends. First came the groom, with a number of his male friends, walking two abreast; then a gorgeous silken canopy, beneath which walked the bride, her person entirely screened. On each side was a man with a drawn sword in his hand, suggesting to the mind thoughts about a lamb led to the sacrifice, or of a criminal conducted to execution. Behind the canopy, in the same order as the men who preceded it, were a number of females of various ages. There were also many attendants with musical instruments. The monotonous, twanging sound of the last, mingled with the shouts of the men; the whining tones and occasional screams of the women; and the flourishes of the swords by those who bore them, presented a singular spectacle; a most extraordinary vocal and instrumental concert, with a yet stranger accompaniment.”

"The same feeling prevented us from cheering as when we launched the boats, although before us was the stream which, God willing, would lead us to our wondrous destination.”

Image: Marko Karoly, The Baptism of Christ in the River Jordan (1840-1841)

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

- William Francis Lynch

- From Virginia to the Dead Sea: Lieutenant William Francis Lynch and the 21st Century

- American Mediterranean: Southern Slaveholders in the Age of Emancipation

- With Sails Whitening Every Sea: A Maritime Empire of Moral Depravity

- Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea. A Journal of Travels in the year 1838

- The Rob Roy On The Jordan, Nile, Red Sea & Gennesareth, &C.: A Canoe Cruise In Palestine And Egypt, And The Waters Of Damascus