Edith Wharton

An author who grew up in an aristocratic family during the Gilded Age. Wharton was raised as a traveler, visiting and living in different European cities with her family. Although she did not attend school, she educated herself using books in her father’s library. She spent her adult years writing prolifically and traveling recreationally, which were both activities funded by her inherited wealth. She often detailed her travels and published these writings as well. Her 1908 travelogue, A Motor-Flight Through France, recounts her journey via automobile across France in 1906 and 1907.

Themes

Need quotes.

- “The motor-car has restored the romance of travel. Freeing us from all the compulsions and contacts of the railway, the bondage to fixed hours and the beaten track, the approach to each town through the area of ugliness and desolation created by the railway itself, it has given us back the wonder, the adventure and the novelty which enlivened the way of ou posting grandparents” (p. 1).

- “…the villages that we missed and yearned for from the windows of the train — the unseen villages have been given back to us” (p. 2).

- “For, after all, if the motorist sometimes misses details by going too fast, he sometimes has them stamped into his memory by an opportune puncture or a recalcitrant ‘magneto’; and if, on windy days, he has to rush through nature blindfold, on golden afternoons such as this he can drain every drop of her precious essence.” (p. 36).

- “Had we visited by rail the principal places named in this itinerary, necessity would have detained us longer in each, and we should have had a fuller store of specific impressions; but we should have missed what is, in one way, the truest initiation of travel, the sense of continuity, of relation between different districts, of familiarity with the unnamed, unhistoried region stretching between successive centres of human history, and exerting, in deep unnoticed ways, so persistent an influence on the turn that history takes. And after all — though some people seem to doubt the fact — it is possible to stop a motor and get out of it” (p. 37).

- “To be back in the roar of traffic, to feel the terrific pressure of those miles of converging masonry, gave us, after weeks of free air and unbounded landscape, a sense of congestion that made the crowded streets seem lowering and dangerous” (p. 170).

- “There are several ways of leaving Paris by motor without touching even the fringe of what, were it like other cities, would be called its slums…. These miraculous escapes from the toils of a great city give one a clearer impression of the breadth with which it is planned, and of the civic order and elegance pervading its whole system; yet for that very reason there is perhaps more interest in a slow progress through one of he great industrial quarters such as must be crossed to reach the country lying to the north- east of Paris” (p. 172).

- “… and in the towns there is almost always some note of character, of distinction — the gateway of a seventeenth century hotel, the triple arch of a church-front, the spring of an old mossy apse, the stucco and black cross-beams of an ancient guild-house — and always the straight lime-walk, square-clipped or trained enberceau, with its sharp green angles and sharp black shade acquiring a value positively architectural against the high lights of the paved or gravelled place” (p. 3-4).

- “Yes — reverence is the most precious emotion that such a building inspires: reverence for the accumulated experiences of the past, readiness to puzzle out their meaning, unwillingness to disturb rashly results so powerfully willed, so laboriously arrived at — the desire, in short, to keep intact as many links as possible between yesterday and tomorrow, to lose, in the ardour of new experiment, the least that may be of the long rich heritage of human experience” (p. 11)

- “The aqueduct, forming part of the extravagant scheme of irrigation of which the Machine de Marly and the great canal of Mainte- non commemorate successive disastrous phases, frames, in its useless lofty openings, such charming glimpses of the country to the southwest of Versailles, that it takes its place among those abortive architectural experiments which seem, after all, to have been completely justified by time” (p. 30)

- “Etampes, our next considerable town, seemed by contrast rather featureless and disappointing; yet, for that very reason, so typical of the average French country town— dry, compact, unsentimental, as if avariciously hoarding a long rich past — that its one straight grey street and squat old church will hereafter always serve for the ville de province background in my staging of French fiction” (p. 33).

- “Our way led across it, by the charming castled town of Pont-de-Chateau, to Clermont-Ferrand, which spreads its swarthy mass at the base of the Puy de Dome — that strangest, sternest of cities, all built and paved in the black volcanic stone of Volvic, and crowned by the sinister splendour of its black cathedral” (p. 55).“Travellers accustomed to the marked silhouette of Italian cities — to their immediate proffer of the picturesque impression — often find the old French provincial towns lacking in physiognomy. Each Italian city, whether of the mountain or the plain, has an outline easily recognisable after individual details have faded, and it is, obviously, much easier to keep separate one’s memories of Siena and Orvieto than of Bourges and Chartres. Perhaps, therefore, the few French towns with definite physiognomies seem the more definite from their infrequency; and Poitiers is foremost in this distinguished group” (p. 88).

- “Built in the twelfth century, by Queen Eleanor of Guyenne, at the interesting moment of transition from the round to the pointed arch, and completed later by a wide-sprawling Gothic front, it gropes after and fails of its effect both without and within. Yet it has one memorable possession in its thirteenth-century choirstalls, almost alone of that date in France — tall severe seats, their backs formed by pointed arches with delicate low-relief carvings between the spandrils” (p. 91).

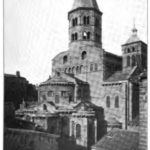

- ‘The gashed walls and ivy-draped dungeons of the rival ruins make an extraordinarily romantic setting for the curious church of Saint Pierre, staunchly seated on an extreme ledge of the cliff, and gathering under its flank the handful of town within the fortified circuit. There is nothing in architecture so suggestive of extreme age, yet of a kind of hale durability, as these thick-set Romanesque churches, with their prudent vault- ing, their solid central towers, the close firm grouping of their apsidal chapels. The Renais- sance brought the classic style into such perma- nent relationship to modern life that eleventh- century architecture seems remoter than Greece and Rome; yet its buildings have none of the perilous frailty of the later Gothic, and one asso- ciates the idea of romance and ruin rather with the pointed arch than with the round” (p. 93).

- “In France, at least, there is perhaps nothing as suggestive of the fortified pleasure-houses of Italy as this gallant castle on the summit of its rock, with the town clustering below, and the vast terrace before it actually forming the roof of its church” (p. 138).

- “And thus one is brought back to the perpetually recurring fact that all northern I art is anecdotic, and has always been so; and that, for instance, all the elaborate theories of dramatic construction worked out to explain why Shakespeare crowded his stage with subordinate figures and unnecessary incidents, and would certainly, in relating the story of Saint John, have included Herod’s “Tray and Sweetheart” among the dramatis person — that such theories are but an unprofitable evasion of the ancient ethnological fact that the Goth has always told his story in that way” (p. 14).

- “But shall we not have gained greatly in our enjoyment of beauty, as well as in serenity of spirit, if, instead of saying ‘this is good art,’ or “’his is bad art,’’ we say ‘this is classic’ and ‘that is Gothic’ — this transcendental, that rational — using neither term as an epithet of opprobrium or restriction, but content, when we have performed the act of discrimination, to note what forms of expression each tendency has worked out for itself?” (p. 17).

- “And somehow, unreasonably of course, one expects the house to bear, even outwardly, some mark of that dark disordered period — or, if not, then of the cheerful but equally incoherent and inconceivable existence led there when the timid Madame Dudevant was turning into the great George Sand, and the strange procession which continued to stream through the house was composed no longer of drunken gentlemen- farmers and left-handed peasant relations, but of an almost equally fantastic and ill-assorted company of ex-priests, naturalists, journalists, Saint- Simonians, riders of every conceivable religious, political and literary hobby, among whom the successive tutors of the adored Maurice — forming in themselves a line as long as the kings in Mac- beth! — perhaps take the palm for oddness of origin and adaptability of manners” (p. 46).

- “The cathedral has its tapestries also — a series from the Brussels looms, attributed to Quentin Matsys, and covering the choir with intricately composed scenes from the life of Christ, in which the melancholy grey-green of autumn leaves is mingled with deep jewel-like pools of colour. But these are accidental importations from another world, whereas the famous Don Quixote series in the Archbishop’s palace represents the culminating moment of French decorative art” (p. 128).

- “They strike one perhaps, first of all — these rosy chatoyanies compositions, where ladies in loosened bodices gracefully prepare to be ‘surprised’— as an instructive commentary on ec- clesiastical manners toward the close of the eighteenth century; then one passes on to abstract enjoyment of their colour-scheme and balance of line, to a delighted perception of the way in which they are kept from being (as tapestries later became) mere imitations of paint- ing, and remain imprisoned — yet so free! — in that fanciful textile world which has its own flora and fauna, its own laws of colour and perspective, and its own more-than-Shakespearian anachronisms in costume and architecture” (p. 128-9).

- “There are two ways of feeling those arts — such as sculpture, painting and architecture — which appeal first to the eye: the technical, and what must perhaps be called the sentimental way. The specialist does not recognise the va- lidity of the latter criterion, and derision is always busy with the uncritical judgments of those who have ventured to interpret in terms of another art the great plastic achievements. The man, in short, who measures the beauty of a cathedral not by its structural detail consciously analysed, but by its total effect in indirectly stimulating his sen- sations, in setting up a movement of associated ideas, is classed — and who shall say unjustly? — as no better than the reader who should pretend to rejoice in the music of Lycidas without under- standing the meaning of its words.” (p. 177).

- “The country itself — so green, so full and close in texture, so pleasantly diversified by clumps of woodland in the hollows, and by streams threading the great fields with light — all this, too, has the English, or perhaps the Flemish quality — for the border is close by — with the added beauty of reach and amplitude, the deliberate gradual flow of level spaces into distant slopes, till the land breaks in a long blue crest against the seaward horizon” (p. 3).

- “Spring comes soberly, inaudibly as it were, in these temperate European lands, where the grass holds its green all winter, and the foliage of ivy, laurel, holly, and countless other evergreen shrubs, links the lifeless to the living months” (p. 73).“It is the season when, through the winter verdure of the Riviera, spring breaks with a hundred tender tints — pale green of crops, white snow of fruit- blossoms, and fire of scarlet tulips under the grey smoke of olive-groves. From heights among the cork-trees the little towns huddled about their feudal keeps blink across the pine-forests at the dazzling blue-and-purple indentations of the coast. And between the heights mild valleys widen down — valleys with fields of roses, acres of budding vine, meadows sown with narcissus, and cold streams rushing from the chestnut forests below the bald grey peaks” (p. 132).

- “Never more vividly than in this Seine country does one feel the amenity of French manners, the long process of social adaptation which has produced so profound and general an intelligence of life. They each had their established niche in life, the frankly avowed interests and preoccupations of their order, their pride in the smartness of the canal-boat, the seductions of the show-window, the glaze of the brioches, the crispness of the lettuce. And this admirable fitting into the pattern, which seems almost as if it were a moral outcome of the universal French sense of form, has led the race to the happy, the momentous discovery that good manners are a short cut to one’s goal, that they lubricate the wheels of life instead of obstructing them” (p. 28-9).

- “This discovery — the result, as it strikes one, of the application of the finest of mental instruments to the muddled process of living — seems to have illuminated not only the social relation but its outward, concrete expression, producing a finish in the material setting of life, a kind of conformity in inanimate things — forming, in short, the background of the spectacle through which we pass, the canvas on which it is painted, and expressing itself no less in the trimness of each individual garden than in that insistence on civic dignity and comeliness so miraculously maintained, through every torment of political passion, every change of social conviction, by a people resolutely addressed to the intelligent enjoyment of living” (p. 29).

- “There are several ways of leaving Paris by motor without touching even the fringe of what, were it like other cities, would be called its slums” (p. 172).

"We had come, at any rate, with the modest purpose of taking a mere bird's-eye view of the region, such a flight across the scene as draws one back, later, to brood and hover; and our sight of the landscape from the Royat balcony confirmed us in the resolve to throw as sweeping a glance as possible, and defer the study of details to our next — our already-projected! — visit" (pg. 58).

Image: Theodore Robinson, A Bird’s Eye View

Places Visited

- “This part of France, with its wide expanse of agricultural landscape, disciplined and cultivated to the last point of finish, shows how nature may be utilized to the utmost clod without losing its freshness and naturalness” (p. 4).

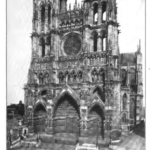

- “At Amiens the autograph consists of one big word: the cathedral” (p. 7).

- “The west front of Amiens says this word with a quite peculiar emphasis, its grand unity of structure and composition witnessing as much to constancy of purpose as to persistence of effort” (p. 11).

- “The town itself — almost purposely, as we felt afterward — failed to put itself forward, to arrest us by any of the minor arts which Arras, for instance, had so seductively exerted. It main-suffering its little shuttered non-committal streets to lead us up, tortuously, to the drowsiest little provincial place, with the usual lime-arcades, and the usual low houses across the way; where suddenly there soared before us the great mad broken dream of Beauvais choir — the cathedral without a nave — the Kubla Khan of architecture” (p. 16)

- “It is, at any rate, an example of what the Gothic spirit, pushed to, its logical conclusion, strove for: the utterance, of the unutterable; and he .who condemns ‘ Beauvais has tacitly condemned the whole theory of art from which it issued” (p. 17).

- “As for Rouen itself, as one passes down its crowded tram-lined quays, between the noisy unloading of ships and the clatter of innumerable cafes, one feels that the old Gothic town one used to know cannot really exist anymore, must have been elbowed out of place by these spreading commercial activities; but it turns out to be there, after all, holding almost intact, behind the dull mask of modern streets, the surprise of its rich medievalism” (17-9).

- “[Fontainebleau] is charming in May, and at no season do its glades more invitingly detain the wanderer; but it belonged to the familiar, the already-experienced part of our itinerary, and we had to press on to the unexplored” (p. #).

- “Certainly, we got a great deal of the Loire as we followed its windings that day: a great sense of the steely breadth of its flow, the amenity of. its shores, the sweet flatness of the richly gardened and vineyarded landscape, as of a highly cultivated but slightly insipid society; an impression of long white villages and of stout conical towns on little hills; of old brown Beaugency in its cup between two heights, and Madame de Pompadour’s M£nars on its bright terraces; of Blois, nobly bestriding the river at a noble bend; and farther south, of yellow cliffs honeycombed with strange dwellings; of Chaumont and Amboise crowning their heaped-up towns; oi memoirs, walled gardens, rich pastures, willowed islands; and then, toward sunset, of another long bridge, a brace of fretted church-towers, and the widespread roofs of Tours” (p. 36).

- “Straight as an arrow, after the unvarying fashion of the French government highway, it runs southeast through vast wheatfields, past barns and farmhouses grouped as in the vanished ‘drawing-books’ of infancy — now touching, now deserting the Indre banks, as the capricious river throws its poplar-edged loops across the plain” (p. #).

- “These little houses are surprisingly picturesque and sentimental; and their mossy roofs, their clipped yews, the old white-capped women who sit spinning on their doorsteps, supply almost too ideal an answer to one’s hopes.” (p. 44)

- “The pictures of Nohant in the Histoire de ma vie are unlike any other description of French provincial manners at that period, suggesting rather an affinity with the somber Bronte background than the humdrum but conventional and orderly existence of the French rural gentry” (p. 45).

- “Our way led across it, by the charming castled town of Pont-de-Chateau, to Clermont-Ferrand, which spreads its swarthy mass at the base of the Puy de Dome — that strangest, sternest of cities, all built and paved in the black volcanic stone of Volvic, and crowned by the sinister splendour of its black cathedral” (55).

“Auvergne, one of the most interesting, and j hitherto almost the least known, of the old French provinces, offers two distinct and equally striking sides to the appreciative traveler: on the one hand, its remarkably individual church architecture, and on the other, the no less personal character of its landscape.” (p. 57).

- “Beyond Laqueille, again, we began to descend by long windings; and at last, turning off from the direct road to Royat, we engaged ourselves in a series of wooded gorges, in search of the remote village of Orcival” (p. 63).

- “The road thence to Royat climbs over the long Col de Ceyssat, close under the southern side of the Puy de Dome, and we looked up longingly at (the bare top of the mountain, yearning to try the ascent, but fearing that our ‘horse-power’ was not pitched to such heights” (p. 65).

- “At this point we left behind us the charming diversified scenery which had accompanied us to the borders of the Loire, and entered on a region of low monotonous undulations, flattening out gradually into the vast wheat-fields about Bourges” (p. 69).

- “Perhaps the spell of Bourges resides in a fortunate accidental mingling of many of the qualities that predominate in this or that more perfect structure — in the mixing of the ingredients so that there rises from them, as one stands in one of the lofty inner aisles, with one’s face toward the choir, that breath of mystical devotion which issues from the very heart of mediaeval Christianity” (p. 71).

- “Spring again, and the long white road unrolling itself southward from Paris. How could one resist the call?” (p. 73).

- “There are several ways of leaving Paris by motor without touching even the fringe of what, were it like other cities, would be called its slums” (p. 172).

- “Through all its profusion of statuary and ornamental carving, the front of Notre Dame preserves that subordination to classical composition that marks the Romanesque of southern France; but between the arches, in the great spandrils of the doorways, up to the typically Poitevin scales of the beautiful arcaded angle turrets, what richness of detail, what splendid play of fancy!” (p. 90).

- “Yet one’s first real sight of them [the Pyrenees] — so masked are they by lesser ranges — is got next day from the terrace at Pau, that astonishing balcony hung above the great amphitheatre of south-western France. Seen thus, with the prosaic English- provincial-looking town at one’s back, and the park-like green coteaux intervening beyond the Gave, the austere white peaks, seemingly afloat in heaven (for their base is almost always lost in mist), have a disconcerting look of irrelevance, of disproportion, of being subjected to a kind of in- dignity of inspection, like caged carnivora in a zoo” (p. 103)

- “Southward the Pyrenees unfold themselves in a long line of snows, and ahead every turn of the road gives a fresh glimpse of wood and valley, of thriving villages and farms, till the last jut of the ridge shows Tarbes far off in the plain, with the dim folds of the Cvennes clouding the eastern distance” (p. 111).

“The Pont du Gard alone would be enough to relegate any town to a state of ancillary subjection. Its nearness is as subduing as that of a great mountain, and next to the Mont Ventoux it is the sublimest object in Provence. The solitude of its site, and the austere lines of the surrounding landscape, make it appear as much on the outer edge of civilisation as when it was first planted there; and its long defile of arches seems to be forever pushing on into the wilderness with the tremendous tread of the Roman legions” (123-4).

- “From Monteimar to Lyons the ‘great north road’ to Paris follows almost con- tinuously the east shore of the Rhone, looking across at the feudal ruins that stud the opposite cliffs. The swift turns of the river, and the fantastic outline of these castle-crowned rocks, behind which hang the blue lines of the Cayennes, compose a foreground suggestive in its wan colour and abrupt masses of the pictures of Patinier, the strange Flemish painter whose ghostly calcareous landscapes are said to have been the first in which scenery was painted for scenery’s sake” (p. 143).

- “…but as we neared the river, and saw before us the curves of the lifted domes, the grey strength of the bridges, and all the amazing symmetry and elegance of what in other cities is mean and huddled and confused, the touch of another beauty fell on us — the spell of “les sewils sacres, la Seine qui ovule.” (p. 171).

- “It is one of the wonders of this rich north* eastern district that the traveller may pass, in a few hours, and through a region full of minor interest, to another great manifestation of medi- eval strength: the fortress of Coucy” (p. 190).

- “Westward from Saint Leu, the valley of the Oise, fruitful but somewhat shadeless, winds on toward Paris through pleasant riverside towns — Beaumont, l’lsle-Adam, and the ancient city of Pontoise; and beyond the latter, at a point where the river flings a large loop to the west, one may turn east again and, crossing the forest of Saint Germain, descend on Paris through the long shadows of the park of Saint Cloud” (p. 201).

"The motor-car has restored the romance of travel. Freeing us from all the compulsions and contacts of the railway, the bondage to fixed hours and the beaten track, the approach to each town through the area of ugliness and desolation created by the railway itself, it has given us back the wonder, the adventure and the novelty which enlivened the way of posting grandparents" (pg.1).

Image: Theodore Robinson, A Bird’s Eye View, 1889